Where he plays another round of flamingo croquet with theology!

Still Lost in Blunderland: Refuting Peter Kwasniewski’s Latest Specious Attack on Ultramontanism

(PART THREE)

by Francis del Sarto

CONTINUED FROM PART 2…

A Brief Review

In PART ONE of this article, we saw how Dr. Peter Kwasniewski discusses Ultramontanism and the Papacy using a strangely un-Catholic approach to the topic. His use of a secular encyclopedia rather than a Catholic theological reference work for his starting point was a telling and, surely, a totally calculated move on his part to help him discredit Ultramontanism. The real traditional Catholic position is at direct odds with his imaginary renderings of theology and Church history.

Contrary to what is suggested in his article, the power of the Pope isn’t something that ebbs and flows through the centuries, but is at all times present in its plenitude. As we showed, this is the magisterial teaching of the Church, to which all Catholics are morally obliged to give their assent.

In PART TWO of this article, we saw how Dr. Kwasniewski selected 19th-century Cardinal John Henry Newman as his anti-Ultramontanist standard bearer. This was another blunder on the professor’s part, which we’ve covered some already but will now be tackling in even more detail. The error hinges on a misapprehension of Newman’s competency on the subject of papal infallibility, because whatever the greatness of his contributions in other areas of theology, the celebrated cardinal had a distinct blind spot when it came to that topic.

Contrary to claims made by Peter Kwasniewski and not a few others, Cardinal Newman’s concern that papal infallibility not be defined at an “inopportune time” was secondary at best to his preference that it never be defined at all but remain in the murky realm of what he considered “theological opinion”. In other words, far from invoking Newman at his best, Dr. K cites the Cardinal at his weakest, as will be demonstrated presently by one of the finest theologians of the past century, and one who had no grudge in any way towards Newman but rather held him in high regard.

We can now move on to the third and final part of this article series.

An Anti-Modernist Theologian Refutes Newman’s & Kwasniewski’s Errors on Papal Infallibility

Near the end of PART TWO we observed that

it would be a huge mistake to conclude that since Newman naturally accepted the new dogma after its solemn promulgation — something all bishops [all Catholics!] had to do under pain of heresy –, that he found reason to celebrate, because in reality he had great animus towards the Ultramontanists who had crafted the conciliar documents, and perhaps even greater antipathy towards the Pope who promulgated them. Nevertheless, it is Cardinal Newman’s views on the First Vatican Council and its decrees that Dr. K wants us to hold high above those of the dreaded Ultramontanists — views that were colored by a friction that had developed between the cardinal and Pius IX over time.

What particularly appeals to Prof. Kwasniewski in Newman’s conflict with Pope Pius IX and the First Vatican Council, unsurprisingly, is how he can equate it — or so he thinks — with the concerns of traditional Catholics over the Second Vatican Council and its aftermath:

It is striking to see one of the most brilliant and saintly [sic] theologians of modern times entertaining such deep misgivings about an ecumenical Council lawfully convoked, about conciliar acts lawfully promulgated, and especially about the reigning pope, whom he hopes will be driven out of Rome or be soon replaced by a better pope. Yet Newman made no attempt to hide where he stood, and although he fully accepted the definition of Vatican I, he also understood it restrictively and modestly, as he argued one should accept all definitions: according to their precise limits and their role within the whole religion of Catholicism.

Those who today have misgivings about the convoking of Vatican II by John XXIII, about various and sundry elements in the sixteen conciliar documents issued under Paul VI, and about the conduct of Pope Francis may take comfort in knowing that such difficulties of mind and problems of conscience are not incompatible with the Catholic Faith or with the virtues of humility and obedience.

(Peter A. Kwasniewski, “My Journey from Ultramontanism to Catholicism”, Catholic Family News, Feb. 4, 2021)

As ridiculous as this attempt is to place Newman’s unjust criticism of a legitimate Roman Pontiff and the sound doctrine of an ecumenical council on a par with traditionalist objections to the rampant heterodoxy represented by Antipope John XXIII’s unlawfully convoked and revolutionary pseudo-council and the fateful “renewal” it engendered in every aspect of Catholic life, it is not surprising to see this coming from “the Kwas”, as some of his fans like to call him.

Hostility towards those vigorously promoting a decree to make papal infallibility a dogma, a position at which he balked, contributed to Newman becoming an energetic but nonsensical obstructionist prior to the passage of the decree, while Dr. Kwasniewski, finding scant aid from Catholic theologians to support his minimization of papal prerogatives, draws an equally nonsensical conclusion that Newman’s high stature all but ensures that the Cardinal’s minority opinion had to be the correct one, when nothing could be further from the truth.

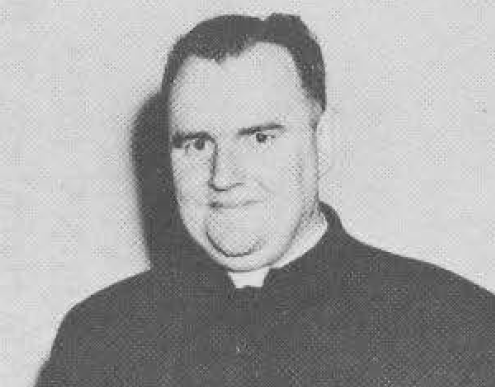

Monsignor Joseph Clifford Fenton (1906-1969). A distingiushed theologian and ardent foe of Modernism, Mgr. Fenton was professor of dogmatic theology at the Catholic University of America and editor of The American Ecclesiastical Review. In the 1960s, he was theological advisor to Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani at the Second Vatican Council. His council diaries include explosive entries against the Modernist subversion of the Faith. Pope Pius XII recognized him for his exquisite theological work. (image: Wikimedia Commons [cropped] / CC BY 3.0)

Fortunately, that truth has been examined in great detail by the esteemed 20th-century American theologian Mgr. Joseph Clifford Fenton (1906-69). A staunch anti-Modernist professor at the Catholic University of America, author, good Vatican II peritus (assisting Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani), recipient of many honors from the Holy See, and long-time editor of The American Ecclesiastical Review, Msgr. Fenton contributed an important essay on Cardinal Newman and the dogmatic definition of papal infallibility in 1945.

Although the article shows Newman the utmost respect, no effort is made to smooth over the gross deficiencies in his thoughts regarding the dogma. Fenton begins:

John Henry Newman’s teaching on the Vatican Council definition of papal infallibility stands apart from all his other contributions to Catholic thought. The great English churchman made valuable additions to the Catholic literature on the history of dogma, on the spiritual life (particularly in the field of priestly perfection), and on the philosophy of education. His works on the genesis of faith and on the process of conversion to Catholic truth have placed the Church forever in his debt. The volumes which treat of these subjects, and which deal with the work of practical apologetic, represent the best and the characteristic thought of the most distinguished convert of the nineteenth century. They are far superior to his writings on the subject of papal infallibility.

Yet, on this happy occasion of the Newman centenary [– he had been received into the Catholic Church on Oct. 9, 1845 –], I believe that it will be not only helpful but actually almost necessary to consider this weakest section of Newman’s teachings. Newman has suffered what is for him the supreme indignity of becoming fashionable. Far more indiscriminate praise than really critical study has been given to his writings. Modern Catholic literature has tended to make a hero of Newman, and has endeavored to justify rather than explain his contentions. As a result his attitude towards the Vatican Council’s definition of papal infallibility has been put on a level with the rest of his teachings.

The effect has been most unfortunate. Some Catholics and not a few of those outside the true Church, have been led to accept on the authority of Newman what, in the last analysis, is an imperfect and inexact statement of the conciliar doctrine.

(Joseph Clifford Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, American Ecclesiastical Review 113, n. 4 [Oct., 1945], p. 300)

Characteristically, Msgr. Fenton isn’t content to look at a few of Fr. Newman’s quotes on the subject but systematically dissects his thinking, with the bulk of the essay broken down into three main sections: “Before the Council”, “During the Council”, and “After the Council”, a format we’ll also follow here.

Before the Council

First cited is a passage from the original text of Discourses on University Education, and it sounds similar in tone to the school boy exuberance found in Dr. Kwasniewski’s early pronouncements on the subject:

Deeply do I feel, ever will I protest, for I can appeal to the ample testimony of history to bear me out, that in questions of right and wrong, there is nothing really strong in the whole world, nothing decisive and operative, but the voice of Him, to whom have been committed the Keys of the Kingdom, and the oversight of Christ’s flock. That voice is now, as ever it has been, a real authority, infallible when it teaches, prosperous when it commands, ever taking the lead wisely and distinctly in its own province, adding certainty to what is probable and persuasion to what is certain. Before it speaks, the most saintly may mistake; and after it has spoken, the most gifted must obey.

(Quoted in Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 301; italics given.)

In his Apologia pro Vita Sua, written in 1864, Newman also asserts his belief in papal infallibility: “It is to the Pope in Ecumenical Council that we look, as to the normal seat of Infallibility” (qtd. by Fenton, p. 301). So far, so good, but then in other places he minimizes the teaching as being only on the level of theological opinion, such as in an 1867 letter to Dr. Edward Pusey: “On the whole then I hold it; but I should account it no sin if, on the grounds of reason, I doubted it” (qtd. in Fenton, p. 302).

Thus Newman sees this teaching at a certain level as really unimportant, quite trivial, even dispensable (“no sin if … I doubted it”), which is at the very crux of his battle with the Ultramontanists: His view would be permissible only if the yet-to-be-defined papal infallibility were merely a theological opinion; otherwise, as part of the Magisterium, though not a dogma, it would still demand the assent of the faithful.

Be that as it may, Neman steadfastly maintained that his view, right up to it being declared a dogma, never varied. On June 27, 1870, nine days after the Vatican Council had issued its definition, he offered the same assertion. “For myself, ever since I was a Catholic, I have held the Pope’s infallibility as a matter of theological opinion” (qtd. in Fenton, p. 302).

It’s at this point that Msgr. Fenton reviews the genesis of Newman’s profound bitterness towards Ultramontanists, ill will coming not from them but almost entirely from him:

It must be remembered that the chief cause of Newman’s fierce opposition to William George Ward, and to Archbishop Manning and the others who advocated a definition of papal infallibility, is his quite emphatic insistence that the doctrine be left on the level of a mere theological opinion. It is perfectly true that he differed from the Archbishop of Westminster and from the other proponents of the Holy Father’s prerogative on questions concerning the limits and the exercise of the Church’s inerrancy. Still, he did not resent their statement of the doctrine of infallibility in a way that differed from his own. What moved him to bitter and continued anger was his opponents’ contention that the thesis on papal infallibility was not a matter of mere theological opinion at all. His polemic was directed primarily, not against an exaggerated or an extremist notion of papal infallibility, but against its presentation or definition as Catholic dogma.

A strange letter from Newman to Ward, written May 9, 1867, brings out this most important element in Newman’s attitude towards the thesis. He accepts with serenity the fact that Ward’s teachings on infallibility differ sharply from his own. Newman’s basic contention is that these differences are unimportant and inevitable. He is infuriated because Ward persists in viewing these differences as important. He could look with equanimity on statements contradicting his own tenets on the subject of the Holy Father’s infallibility as long as these statements were presented as opinions which could be accepted or rejected freely. He is intolerant and indignant when such teachings are offered as dogmatic truth.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 302-303; underlining added.)

Mgr. Fenton then produces part of the letter, which shows how annoyed Fr. Newman was with those holding a position contrary to his: “I have considered one phenomenon in you to be ‘momentous,’ nay, portentous, that you will persist in calling the said unimportant, allowable, inevitable differences, which must occur between mind and mind, not unimportant, but of great moment” (qtd. in Fenton, p. 303).

Cardinal Newman then chastises Mr. Ward for his “uncatholic” (Newman’s word) view that the doctrine of papal infallibility is more than just an unimportant opinion that need never be defined, and for “even exalting your opinions into dogmas.” Ward never did that, but it’s instructive that Newman insists on speaking of Ward’s “opinions”, because while Ward did not see infallibility as a dogma, given that it hadn’t yet been defined, he certainly held it as being above mere opinion. If anything, what’s being exhibited is Newman projecting his own thoughts on Ward.

“The letter ends”, writes Fenton, “on that note of harshness which Newman seemed to reserve for those who differed from him on the question of papal infallibility” (p. 303). Actually, he goes so far as to accuse Ward of “what I must call your schismatical spirit” (qtd. in Fenton, p. 303; italics added). It appears that Newman had discovered a new criterion for schism: In addition to refusing submission to the Roman Pontiff or communion with members of the Church, now refusal to agree with him rendered one at least suspect of the offense!

There was something paradoxical in Newman’s stance. Mgr. Fenton explains:

It is Newman’s contention that, should the doctrine of papal infallibility really belong to the divine message, the purity of his own faith is saved by the fact that he believes it implicitly in accepting as the revealed word of God everything thus presented by the Catholic Church. Thus Newman’s stand did not involve any denial on his part that the doctrine of papal infallibility is actually a part of divine public revelation. He was perfectly willing to admit that this teaching was probably included in God’s message to mankind. His whole polemic was directed towards withholding from the doctrine of papal infallibility anything more than an implicit assent of divine faith. Explicitly he would concede to it only the status of an opinion.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 304)

That is the gist of what Newman told Mr. Henry Wilberforce in this passage of a letter dated July 21, 1867:

…[I]f I am told: “The Church has spoken,” then I ask when? and if, instead of having anything plain shown me, I am put off with a string of arguments, or some strong words of the Pope himself, I consider this a sophistical evasion, I have only an opinion at best (not faith) that the Pope is infallible, and a string of arguments can only end in an opinion—and I comfort myself with the principle: “Lex dubia non obligat” [“a doubtful law does not bind”]—what is not taught universally, what is not believed universally, has no claim on me—and, if it be true after all and divine, my faith in it is included in the implicita fides [implicit faith] which I have in the Church.

(Quoted in Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 305; italics given.)

Given his concession that papal infallibility may indeed be part of the Deposit of Faith, it’s puzzling, to say the least, that Fr. Newman was so adamant that it never be pronounced a dogma. But indeed he was adamant, to the point of being intemperate in his language. About this, Fenton observes:

Objecting to the practice of proposing the doctrine of papal infallibility as a dogma, although he was ingenuously ready to admit that it might be numbered among those truths included in the deposit of divine public revelation, the full force of Newman’s wrath was turned, long before the actual convening of the Vatican Council, upon those who were urging that the Council define papal infallibility as a dogma. As early as November 10, 1867, we find Newman complaining of the “intrigue, trickery, and imperiousness” of those who favored a definition of the Holy Father’s infallibility. This strong language was occasioned by Archbishop Manning’s Pastoral.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 305)

Newman’s complaints were not confined to private missives, as he promoted the dissemination of brochures such as Idealism in Theology by Fr. Ignatius Ryder, which Fenton describes as “a personal attack on Mr. William George Ward, whose writings on papal infallibility were understood to have the support of Archbishop Manning” (Fenton, p. 306). What’s disturbing here is that Newman is shown to have made two contradictory explanations of how Fr. Ryder came to write the piece: either “entirely on his [Ryder’s] own idea, without any suggestion (as far as I know) from anyone” (1845 letter to Mr. Ward; qtd. in Fenton, p. 306), or where Newman takes credit for “my share in it” (1867 letter to Canon Walker; qtd. in Fenton, p. 306).

Sadly, it isn’t just in his theology here that Newman is shown at his worst; he could be, as already seen, quite vicious in his invective against proponents of the declaration, but also bend over backwards to excuse any of his anti-infallibility allies. Let’s just say that if a real process for canonization was begun, the devil’s advocate could find a sizable amount of grist for the mill in this part of his life before moving on to anything else. (As a brief aside, it is noteworthy that Dr. Kwasniewski is happy to refer to Cardinal Newman as “St. John Henry Newman”, yet he is not quite so generous when it comes to “St.” Paul VI — even though both of them were canonized by the same “Pope”, Francis.)

On this, Fenton remarks:

Ryder had foolishly characterized himself as a Gallican. Newman will not condemn even this absurdity. For a Review in which such writers as the infamous [Lord John] Acton sought to turn Catholics away from the Vicar of Christ, Newman can find no harsh words. The only vehemently bitter expressions he is able to form during all this period of conflict are directed against the proponents of the Holy Father’s infallibility.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 306)

There was a marked inconsistency in Newman’s approach that some might even characterize as hypocrisy. Beyond that we see him spinning his own utterly baseless Victorian Era conspiracy theory (yes, Newman actually uses the word “conspiracy” in this regard) about how the hundreds of those supporting the definition’s ultimate passage were evildoers bent on taking action “against the theological liberty of Catholics.” (If his fitness for being raised to the Cardinalate had been based solely on his delusional thoughts about this, instead of presenting him with the red hat, Pope Leo XIII should have made it a tin foil hat!)

As Msgr. Fenton notes:

A sharp attack on the doctrine of papal infallibility received Newman’s support. A sharp and decisive rejoinder to that attack drew only his lofty disapproval. Acerbity was acceptable, but only in anti-infallibilist writings.

An outstanding characteristic of Newman’s attitude to the question of papal infallibility prior to the Vatican Council is his unrelenting and violent aversion for the proponents of the definition. One can search in vain through his writings of this period for one scant word of approval, for one admission that they might have had some not-too-outrageous reason for believing that the doctrine should be defined. For some reason or other Newman seemed to regard it as a sacred duty to oppose the projects of his Metropolitan. Writing about Ryder’s pamphlet to Fr. St. John, who was then in Rome, Newman speaks thus about the Archbishop[:]

As to clamour and slander, whoever opposes the three Tailors of Tooley Street [Manning, Ward, and Vaughan] must incur a great deal, must suffer—but it is worth the suffering if we effectually oppose them . . .

Newman considered that, in opposing Archbishop Manning and his followers, he was fighting a “formidable conspiracy, which is in action against the theological liberty of Catholics”…

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 306-307; italics given.)

Is attacking “theological liberty of Catholics” really code for opposition to the opinions of Fr. Newman and his fellow obstructionists? Based on what’s been covered so far, the possibility cannot be ruled out. In reviewing Fr. Newman’s thoughts prior to the Council, which at their worst approach sheer rantings, it is difficult to think they came from the same mind that was capable of writing such lofty prose and poetry.

Bringing this back around to the primary subject of the current study, let’s continue to bear in mind that in “My Journey from Ultramontanism to Catholicism”, Peter Kwasniewski errs by typical shortcuts in scholarship, taking Newman’s version of events uncritically, while setting up as a strawman Ward’s obviously tongue-in-cheek remark about desiring a new Papal Bull to go with his morning paper and breakfast, as somehow indicative of the Ultramontanists’ supposed goal of papal infallibility on steroids.

On that note, Kwaniewski states that Newman “was distressed at this exaggeration of the papal office and its function. The papacy risked being turned into an industrial factory of new pronouncements and new directives on every subject under the sun.” That Dr. K accepts such nonsense without doing the requisite digging of any legitimate researcher is troubling, but time and again we’ve seen that this is how the man operates: By skimping on documentation, he’s able to insert more of his own opinions.

Finally, the professor makes the gargantuan blunder of availing himself for his impeccable source the absolute worst possible version of John Henry Newman. He falls into the category of unfortunates who, writes Msgr. Fenton, “have been led to accept on the authority of Newman what, in the last analysis, is an imperfect and inexact statement of the conciliar doctrine.”

During the Council

After reading the foregoing about Newman and papal infallibility, one could only hope for more gentlemanly behavior to emerge as the Council unfolded. Alas, there was no improvement during the sacred assembly, despite clear evidence that ought to have made him rethink his extremism. Recall that in his article Kwasniewski quotes a Fr. Newman letter approvingly in which the latter rails about how a “tyrant majority is still aiming at enlarging the province of Infallibility” (in Letters and Diaries, vol. XXV, p. 192; italics Newman’s). Here the professor again expects his readers to take the English convert’s observation as unimpeachable gospel, yet without providing the slightest bit of evidence that this is an accurate account of what actually transpired at the Council.

This letter, by the way, is the same regrettable missive in which Fr. Newman, as we saw in PART TWO, expressed his hope that Pope Pius IX be “driven from Rome” — and he didn’t mean in a limousine — or even die so as not to be able to continue the Council. The notion that the Pope and the 533 bishops who supported passage of the decree — the “tyrant majority”, according to Newman — comprised a cabal of close-minded anti-intellectuals who sought to put a papally-centered stranglehold on the minds and spirits of Catholics but who fortunately had the lights of academia lined up against them, was a false narrative that the anti-infallibalists made every effort to foist on the faithful.

Unfortunately for Fr. Newman (and Dr. Kwasniewski), but fortunately for the Catholic Church, this myth was quickly dashed, even before it had a chance to gain much traction. Writes Msgr. Fenton:

The first session of the Vatican Council was held on December 8, 1869. Two weeks later the Rector, the Dean, and ten of the Professors of Louvain’s great theological faculty addressed to the Council a petition that the Fathers should define as a dogma of faith the doctrine that “when he prescribes to the universal Church of Christ in solemn definition that some dogma is divinely revealed and to be received with divine faith, or when he condemns some assertion as contrary to divine revelation, that the Roman Pontiff, the successor of St. Peter, cannot err.” The Louvain petition proudly listed the names of the glorious lights of the ancient faculty who had held this doctrine, naming James Latomus, John Driedo, Ruard Tapper, Jodocus Ravestyn, John Hessels, William Lindanus, Martin Rythovius, Cornelius Jansen the Bishop of Ghent, Thomas Stapleton, William Estius, John Malderus, and Christian Lupus. On January 7, 1870, all the Bishops of Belgium, led by Archbishop Dechamps of Malines, presented the Louvain petition to the Council. The Louvain action rendered impossible, once and for all, any serious contention that the world of scholarship was opposed to the definition.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 307-308)

And yet over 150 years later it hasn’t stopped Peter Kwasniewski from echoing such nonsense as Newman being “distressed at this exaggeration of the papal office and its function. The papacy risked being turned into an industrial factory of new pronouncements and new directives on every subject under the sun”, the professor writes.

Furthermore, he asserts that Newman

knew that a party of “ultramontanes” was busy pushing a theologically unsound, philosophically unreasonable, historically untenable, and ecclesiastically damaging version of papal inerrancy that threatened to confuse the pope’s office with divine revelation itself, rather than seeing him more modestly as the guardian of tradition and the arbiter of controversy.

(Kwasniewski, “My Journey from Ultramontanism to Catholicism”)

All of what he writes here is pure rubbish, and he is hoisted on his own petard because it isn’t the Ultramontanists, it is Newman and Kwasniewski who end up being theologically unsound, philosophically unreasonable, and historically untenable, in addition to being ecclesiastically damaging in their opposition. And this can be demonstrated by comparing the definition proposed by the Louvain faculty that was presented at Vatican I’s opening in January 1870 with the Council’s dogmatic decree a little over half a year later:

Louvain Version

…when he prescribes to the universal Church of Christ in solemn definition that some dogma is divinely revealed and to be received with divine faith, or when he condemns some assertion as contrary to divine revelation, that the Roman Pontiff, the successor of St. Peter, cannot err.

Official Version promulgated by the Council

…when the Roman Pontiff speaks EX CATHEDRA, that is, when, in the exercise of his office as shepherd and teacher of all Christians, in virtue of his supreme apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole Church, he possesses, by the divine assistance promised to him in blessed Peter, that infallibility which the divine Redeemer willed his Church to enjoy in defining doctrine concerning faith or morals. Therefore, such definitions of the Roman Pontiff are of themselves, and not by the consent of the Church, irreformable.

(First Vatican Council, Dogmatic Constitution Pastor Aeternus, Chapter 4)

The alarmism of Newman and Kwasniewski is shown to be baseless. Although the wording differs from one version of the definition to the other, the basic concepts expressed are clearly the same. If anything, the final version as defined is less specific than that proposed by the University, given that it makes no reference to the condemnation of errors, though that can perhaps be inferred.

There is no overreach of power indicated in either of them, which is the great bugaboo, the phantom menace of Newman and Kwasniewski. Allowances can be made for the former, although at times his grumbling comes across as prideful; but Dr. K doesn’t get off so easily. With the benefit of over a century-and-a-half of hindsight to show him the error of his way, he simply refuses to let go of his fictionalized version of Ultramontanism, because he uses it to prop up the creaky edifice of his Anti-Sedevacantism, which is what his excursions into Blunderland are ultimately about.

Blundering, sadly, was also something Fr. Newman was engaged in at the start of the Council in January 1870, as testified to by a typically wrongheaded letter to Bishop William Ullathorne (1806-1889), related by Msgr. Fenton as follows:

He [Newman] complains that “an aggressive insolent faction” should be allowed “to make the heart of the just to mourn, whom the Lord hath not made sorrowful,” and informs his Ordinary that “some of the best minds” are reacting, among other ways, by becoming “angry with the Holy See for listening to the flattery of a clique of Jesuits, Redemptorists, and converts.” He adverts to “the store of pontifical scandals in the history of eighteen centuries” and indicates the “blight’’ which is falling upon certain Anglican ritualists at even the prospect of the definition. He so far forgets himself as to declare that what the infamous and scurrilous anti-Catholic lecturer Murphy had inflicted upon the Church, the distinguished journalist, M. Veuillot, was indirectly bringing upon it now, presumably through his advocacy of the definition.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 309)

When Newman states that “some of the best minds” are becoming “angry with the Holy See”, one may wonder if those minds include his own. Evidently, he was not aware of another group of the best minds, namely, the Louvain faculty, who were wholeheartedly supportive of Pius IX. (Again, none of this from the tunnel-visioned Kwasniewski, who does not bother to give this side of the Council, making it seem as though it never existed. He has his own narrative to spin, as one-sided and misleading as it is, and he will not vary from it to be more historically accurate.)

Newman’s letter was leaked to the press, and became a sensation: “On March 14, The Standard, an English newspaper, published a report that Newman had written to his Bishop ‘stigmatising the Promoters of Papal Infallibility as an insolent, aggressive faction’,” Fenton writes further.

Initially, the English theologian disavowed the term, suggesting that the paper was mistaken in attributing it to him, but then, when confronted with proof, he went into what today we might call “damage control” mode:

Two days later the reporter who had made the statement attributing the expression “insolent, aggressive faction” to Newman returned to the case and reaffirmed his belief that the words had actually been employed. On March 22, Newman wrote again to the Standard, acknowledging that its reporter had been correct in his statement. This time he insisted that when he had spoken of the faction, he had “neither meant that great body of Bishops who are said to be in favour of the definition of the doctrine, nor any ecclesiastical order or society external to the Council.” Apparently still relying on the bad copy, and forgetting that they had been classed, along with Redemptorists and converts, as components of a clique engaged in flattering the Holy Father, Newman solemnly announced: “As to the Jesuits, I wish distinctly to state that I have all along separated them in my mind, as a body, from the movement which I so much deplore.” The “faction” turns out to be “a collection of persons drawn together from various ranks and conditions in the Church.”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 310)

Surely we are permitted to seriously question Newman’s sincerity when he writes that he didn’t mean to include “that great body of Bishops who are said to be in favour of the definition of the doctrine” as part of the faction he condemns, given that just a few short months later he was berating them as forming the “tyrant majority”. Damage control, indeed.

But he couldn’t just let the topic rest; it was clearly an obsession for him, and an unhealthy one, at that. Msgr. Fenton recounts:

His condemnation of the leaders in the fight for the definition became more virulent than ever. “Nothing can be worse,” he writes, “than the conduct of many in and out of the Council who are taking the side which is likely to prevail.” These leaders “have been taking matters with a very high hand and with much of silent intrigue for a considerable time.” Even the despicable writings of such as Acton can be explained by Newman as “the retributive consequence of tyranny.’’ Writing on the subject of the definition to David Moriarty, Bishop of Kerry, like Bishop Clifford both an intimate friend of Newman and a vigorous opponent of the Majority policy, he declares that he “cannot bear to think of the tyrannousness and cruelty of its advocates—for tyrannousness and cruelty it will be, though it is successful.”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 311)

Note that this is the second time in our quotes of Fenton that he alludes to Lord Acton (1834-1902) and Newman’s attitude towards him. Acton was an avid anti-Ultramontanist historian, as is evident from him being described here as “infamous” and responsible for “despicable writings”. He can legitimately be called a “Liberal Catholic”, who opposed papal power and the Vatican I dogma. His well-known “power corrupts” quote was written with the Papacy in mind, along with secular monarchies. He spent six years in Munich as the student of the Church historian Johann Joseph Ignaz von Döllinger (1799-1890), in whose home he resided. (Döllinger is, of course, best known for refusing to accept the dogma of papal infallibility defined by the Vatican Council, which got him excommunicated in 1871. He is loosely associated with the sect of the so-called “Old Catholics”, which he never joined, however.)

In 1859, Lord Acton took over the editorship of The Rambler from Newman, moving it leftward after he transformed it into The Home and Foreign Review, about which Fr. Herbert Thurston, S.J., writes, “The ultra liberal tone of this journal gave offence to ecclesiastical authorities, and Acton eventually judged it necessary to discontinue its publication…” (Catholic Encyclopedia). Fr. Newman’s sympathies towards Lord Acton don’t show him at his best, at his most loyal to the Holy See, and we wonder how much of this was unknown to Pope Leo when he raised him to the Cardinalate. Acton and Newman, writes Fenton, had much the same disdain for the definition:

Acton, who was in constant touch with Newman during the time of the infallibility debates and who was sympathetic to Newman’s attitude, seems to have considered the great Oratorian’s explanation of the Vatican decrees as being, for all intents and purposes, an emptying of their content. Writing to “dear Mr. Gladstone” in December 1874, Acton made no secret of the fact that it was his wish “to make the evils of Ultramontanism so manifest that men will shrink from them, and so explain away or stultify the Vatican Council as to make it innocuous.” After the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk had appeared, Acton, apparently still unwilling to do other than “explain away” the Vatican definitions, announced to Lady Blennerhassett that ‘“Newman’s conditions would make it possible, technically, to accept the whole of the decrees.” Even before the Council had made its definition, Newman had written to Mr. O’Neill Daunt, contending that “if anything is passed, it will be in so mild a form, as practically to mean little or nothing.’”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 319)

Oddly (or perhaps not), Newman was ready to bestow upon himself a quasi-infallibility in his struggle against papal infallibility. Again, Msgr. Fenton exposits:

One of the most amazing factors in Newman’s opposition to the definition during the time of the Council was his repeated conviction that he and his followers ought to act in this debate as though they were themselves gifted with infallibility. He expresses this sentiment once in the letter to De Lisle, and again in a letter to Fr. Whitty. He thus expresses himself in the latter communication.

One can but go by one’s best light. Whoever is infallible, I am not; but I am bound to argue out the matter and to act as if I were, till the Council decides; and then, if God’s Infallibility is against me, to submit at once, still not repenting of having taken the part which I felt to be right, any more than a lawyer in Court may repent of believing in a cause and advocating a point of law, which the Bench of Judges ultimately give against him.

In this case we have either an inept analogy, or a real index of a mistaken attitude on the part of Newman. A lawyer may argue a case before the highest tribunal. In the event that the decision is given against him, he is of course bound to accept that decision. But in no case is he bound to think that the court has decided correctly. He can still be convinced that his own side was the right one, and he can legitimately hope that at some future date the tribunal will incline towards the views which he has defended. There is no legitimate parallel between this case and that of a man who has taken a side against which an infallible dogmatic decision of the Catholic Church is issued. It is unfortunate that Newman imagined that such an analogy was valid.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 311-312)

Clearly, for all Newman’s excellent theological insights, he is quite purblind in this most crucial matter: He is resolute about holding to the wrong side of this question, as Fenton shows, and despite his later acceptance of the dogma, there is no evidence that he ever believed himself wrong.

Yet he takes an even deeper plunge into error:

Passing to what he regards as specific reasons against the definition of papal infallibility by the Council, Newman adduces four points. The first of these is merely one of the cardinal principles of the old Gallicanism. The advocates of the definition are warned that they “must not flout and insult the existing tradition of countries.” He denies that the traditions of Ireland and England are on the side of papal infallibility, and insists that what he terms Ultramontane views are comparatively recent both in those countries and in France and Germany. In voicing this opinion Newman manifested, as perhaps nowhere else, the spectacular intellectual weakness of his own cause. He appeals to what is at best a highly suspect theological principle, and, in branding the “UItramontane” views as “recent” he showed little knowledge of the history of scholastic theology.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 312; underlining added.)

Newman next returns to his claim of a “conspiracy”:

The second point alleged in this letter consists in a rehash of the old attack against the promoters of the definition. This time the particular charge is that they had kept the other members of the Council from knowing about their purpose to work towards the

definition. “I declare,” wrote Newman, “unless I were too old to be angry, I should be very angry.” He recollects a statement attributed to poor Msgr. Talbot to the effect that what made the definition of the Immaculate Conception such an acceptable thing was the fact that it opened the way towards a definition of the Holy Father’s infallibility. Newman professed himself shocked at the thought and, meditating “on such crooked ways,” he turned to the consideration of our Lord’s warning about scandal. Never once did it seem to enter his mind that there was even a faint chance that his own conduct in the affair might possibly have given scandal.(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 313)

Msgr. Fenton then sees a seeming application of Hegelian dialectic in Fr. Newman’s method of argumentation:

The third point is interesting. It was Newman’s contention that the intense theological study which had preceded the Ineffabilis Deus “had brought Catholic Schools into union about it, while it secured the accuracy of each.” He believed that each of the two schools of thought which had previously existed on the subject of our Lady’s Immaculate Conception “had its own extreme points eliminated, and they became one, because the truth to which they converged was one.’” Newman seemed to assert that the only means of doctrinal progress was along the Hegelian lines of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. He apparently imagined that when two groups are opposed on some issue, the ultimate resolution can come only through a sort of compromise, in which the “extreme” points of both opposing theories are abandoned while all the contestants unite in their adherence to a middle position. He seems not to have considered the possibility of a situation in which two parties might debate, and one turn out to have defended a truth which the other attacked.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 313; underlining added.)

And, then, Newman’s concluding point:

The final argument adduced in the letter to Fr. Whitty takes the form of a protest against the definition on the grounds that it will be “dated,” as meant merely to give support to the Syllabus. Furthermore he finds that it is inexpedient for England since its very prospect has proved disquieting to the ultra pontifical Mr. Gladstone, and to a certain unsavory, convent-baiting politico named Newdegate.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 313-314)

The suggestion that the definition will become “dated” because in Newman’s mind it had no reason to exist save to prop up the Syllabus of Errors is at once ludicrous and desperate. That an intellect as normally keen as his would be reduced to making such a claim is distressing.

His other claim, that the definition would be “inexpedient” for Catholics in England has more basis in fact, as it caused William Gladstone, the anti-Catholic Prime Minister to increase his savage attacks upon the Church in the form of pamphlets such as The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance (to his credit, Fr. Newman would respond in 1875 with his 150-page Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, although, ironically, Gladstone’s assertion that the definition would take away the mental liberty of Catholics isn’t far removed from what Newman had himself earlier said about it).

“Newdegate” referred to Charles Newdegate, a member of Parliament who opposed the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England and called for a commission to be formed to look into convent life. That call for intrusions into religious communities, however, was met with strong resistance, as noted in a Pilot article, when “more than 600 Catholic ladies of distinction have signed an indignant protest against the idea of a commission being appointed to examine the convents in England” (vol. 33, n. 22, May 28, 1870).

Regardless of how “disquieting” the definition was to these men, they hardly represented all Englishmen, and Catholics as a whole were largely protected from these radical voices since the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. Recall, too, that other respected Catholics of the day, such as Abp. Henry Edward Manning and William George Ward, were not voices of doom like Newman, and their calmer, sounder assessment of the situation would prove to be the correct one.

It is astounding how shortsighted Fr. Newman could be, when in sheer pigheadedness he resolved to oppose a perfectly sound position being advanced by the Pope, the overwhelming majority of the world’s bishops, and many theologians of distinction. Needless to say, posterity has not been kind to Newman’s strange theories.

To borrow from a point made earlier in the present study, in these attacks on the “Ultramontane” faction promoting the definition, Newman is shown to be, in Peter Kwasniewski’s terms, “theologically unsound, philosophically unreasonable, historically untenable, and ecclesiastically damaging…”; namely, manifesting all of the weaknesses that are falsely attributed in “My Journey from Ultramontanism to Catholicism” to those at the Council who held the correct position on papal infallibility.

After the Council

“On July 18, 1870”, writes Msgr. Fenton, “the Vatican Council adopted and promulgated the constitution Pastor aeternus containing the Catholic definition of papal infallibility…

To Newman, who had hoped against hope that the definition would never be made, the act of the Council came as a stunning blow. It was not long however before he manifested the attitude which he was to adopt towards the new definition.

At first he refused adamantly to accept the definition as a de fide pronouncement. It remained for him in the status of an opinion. The acts of a Council, he contended, do not seem certainly binding until they are promulgated at the termination of that gathering. Before the end of the Council, things could be expected to right themselves.

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 314)

As late as August 8 he still found ways to foot-drag on his acceptance of the definition, finding every excuse not to accept it as de fide, kicking and screaming to the bitter end:

I want to know what the Bishops of the minority say on the subject, and what they mean to do. As I have ever believed as much as the definition says, I have a difficulty in putting myself into the position of mind of those who have not. As far as I can see, no one is bound to believe it at this moment, certainly not till the end of the Council. This I hold in spite of Dr. Manning. At the same time, since the Pope has pronounced the definition, I think it safer to accept it at once. I very much doubt if at this moment—before the end of the Council, I could get myself publicly to say it was de fide, whatever came of it—though I believe the doctrine itself.

(Quoted in Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 314)

There is something quite empty about John Henry Newman’s repeated protests that he had “ever believed as much as the definition says”, and “I believe the doctrine”, and that’s because it was always just a “theological opinion” for him, something he had no obligation to accept as part of the Magisterium, and indeed something that he insisted was “no sin if … I doubted it”.

Here it is worth examining Newman’s “just a theological opinion” claim, since the English convert was obviously in error to think and publicly proclaim that papal infallibility was a mere opinion. If anything, it was merely his opinion that the teaching was only an opinion, and in that opinion he was quite mistaken to boot!

Fr. Patrick Toner, under the subheading “Proof of papal infallibility from Tradition”, in his Catholic Encyclopedia article on the topic corrects Newman’s “opinion” fallacy when he writes:

And what is still more important, is the explicit recognition in formal terms, by councils which are admitted to be ecumenical, of the finality, and by implication the infallibility of papal teaching.

- Thus the Fathers of Ephesus (431) declare that they “are compelled” to condemn the heresy of Nestorius “by the sacred canons and by the letter of our holy father and co-minister, Celestine the Bishop of Rome.”

- Twenty years later (451) the Fathers of Chalcedon, after hearing Leo’s letter read, make themselves responsible for the statement: “so do we all believe . . . Peter has spoken through Leo.”

- More than two centuries later, at the Third Council of Constantinople (680-681), the same formula is repeated: “Peter has spoken through Agatho.”

- After the lapse of still two other centuries, and shortly before the Photian schism, the profession of faith drawn up by Pope Hormisdas was accepted by the Fourth Council of Constantinople (869-870), and in this profession, it is stated that, by virtue of Christ’s promise: “Thou art Peter, etc.”; “the Catholic religion is preserved inviolable in the Apostolic See.”

- Finally the reunion Council of Florence (1438-1445), repeating what had been substantially contained in the profession of faith of Michael Palaeologus approved by the Second Council of Lyons (1274), defined “that the holy Apostolic see and the Roman pontiff holds the primacy over the whole world; and that the Roman pontiff himself is the successor of the blessed Peter Prince of the Apostles and the true Vicar of Christ, and the head of the whole Church, and the father and teacher of all Christians, and that to him in blessed Peter the full power of feeding, ruling and governing the universal Church was given by our Lord Jesus Christ, and this is also recognized in the acts of the ecumenical council and in the sacred canons (quemadmodum etiam . . . continetur).

Thus it is clear that the Vatican Council introduced no new doctrine when it defined the infallibility of the pope, but merely re-asserted what had been implicitly admitted and acted upon from the beginning and had even been explicitly proclaimed and in equivalent terms by more than one of the early ecumenical councils. Until the Photian Schism in the East and the Gallican movement in the West there was no formal denial of papal supremacy, or of papal infallibility as an adjunct of supreme doctrinal authority, while the instances of their formal acknowledgment that have been referred to in the early centuries are but a few out of the multitude that might be quoted.

(Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. “Infallibility”; underlining added.)

Now, while it’s true that Newman said he always implicitly held this “opinion” (again, his word) to be true, he fell short of adhering to it as Catholics are required to do, that is, to give his firm assent to it inasmuch as it is the teaching of the Church, and, as Fr. Toner puts it, “explicitly proclaimed and in equivalent terms by more than one of the early ecumenical councils”. How he could have been ignorant of the fact that papal infallibility was definitely a Church doctrine — not an opinion — is baffling to say the least. In the final analysis, the “theological opinion” claim was a serious theological error.

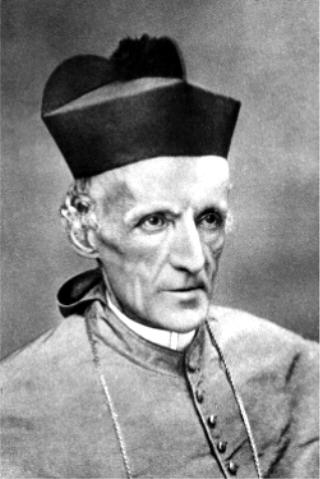

Pope Pius IX (r. 1846-1878), who convened the First Vatican Council in 1869, is praised by Catholic historians as a wise and courageous pontiff, defending the Church at a time when the political currents of the day buffeted the Barque of Peter, yet Newman and Kwasniewski have strangely vilified him. (image: Wikimedia Commons / public domain)

Returning to Msgr. Fenton’s study:

Less than a week after the definition had been made by the Council, Newman had confided his attitude to one of his friends. “I saw the new definition yesterday,” he wrote, “and am pleased at its moderation—that is, if the doctrine in question is to be defined at all. The terms are vague and comprehensive; and, personally, I have no difficulty in admitting it.”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 314-315)

Here, we wonder precisely what Fr. Newman had in mind when he used the term “vague”, because vague the definition certainly is not, as it sets out very specifically all the criteria necessary before a doctrine on faith or morals defined by a pope becomes dogma. Yes, there could be more in the order of details, but what is contained in it is very clear. In the final analysis, perhaps it’s only “vague” because that’s how Newman wanted it to be.

Newman being “pleased at its moderation” goes along with Prof. Kwasniewski’s unwarranted relief that the dreaded Ultramontanists had failed to carry the day with what is falsely asserted as their goal that through the definition they would create an “industrial factory of new pronouncements” from the Pope. Of course, typically in a Dr. K essay the author eschews anything approaching serious research to defend his claim, favoring, instead, tenuous suggestions, such as Mr. Ward’s obviously tongue-in-cheek remark about wanting daily papal bulls to read with his morning toast and tea, as mentioned earlier.

Kwasniewski’s only other “proof” is that the moderate approach agreed upon was somehow semi-miraculous, and that the Church barely avoided the spectre of unbridled, metastasizing papal infallibility as posed by Fr. Newman’s paranoid hand-wringing about the “tyrant majority”. As has been shown above, but which we’ll re-emphasize here, the Newman-Kwasniewski nonsense flies in the face of the reality that a very moderate document for the definition had already been presented to Pope Pius IX and the Council Fathers by Louvain University’s faculty several months before the promulgation of the dogma, the restrained language of which may well have served as a template of sorts for the Council’s final decree.

Incredibly, writes Msgr. Fenton, Newman still remained shamefully in stubborn resistance to the definition as being something he didn’t feel obliged to accept:

The old passion for admitting the doctrine exclusively as an opinion appears even in this letter. Newman sets himself to inquire whether or not the definition comes to him “with the authority of an Ecumenical Council.” He answers this question in the negative. The authority of an Ecumenical Council is certainly accorded only to those doctrines which Councils proclaim with moral unanimity, according to Newman. At the moment when the Vatican Council proclaimed the doctrine of papal infallibility it did not possess, as far as he was able to judge, the moral unanimity which would have made it necessary for all Catholics to accept its definition with the assent of divine faith. All of definition’s claim to be a de fide pronouncement was said to hinge upon the future conduct of the Minority Bishops, on later sessions of the Council, and finally upon the reception accorded the conciliar definition by “the whole body of the faithful.”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 315)

If the whole question of whether or not the definition becomes de fide rests, ad absurdum, upon the tiny handful of holdout bishops, as imagined by Newman, then should we not be speaking, more properly, of the tyrant minority that was able to hold a dogma hostage?

No wonder Dr. Kwasniewski is so onboard with Fr. Newman regarding the dogma, because the latter also seems to find a certain satisfaction in moving the doctrinal goal posts to suit his own prejudices, just as we see the former and the recognize-and-resist lobby continue to conjure up their own un-Catholic version of the Papacy in general. For far too long we see him taking the stance of making this more a matter of the Papacy according to Cardinal Newman, and not according to Pope Pius and the Council.

One hundred and fifty years before Kwasniewski’s silly article, Newman had fallen down the same rabbit hole to Blunderland, landed squarely on his head, and came up with an exposition of his view of papal infallibility that provides grounds to seriously question further his orthodoxy concerning the subject. Msgr. Fenton continues:

Later he was willing to accord it the status of a dogma, but only under conditions which could be made to justify his previous stand. Had he not expressed himself as not too greatly concerned with questions about the seat and the limits of infallibility? Was not his own favorite and ultimate organ of infallibility the consent of the universal Church, the factor described in the phrase “Securus judicat orbis terrarum” [“the whole world judges right”], the expression so intimately connected with his own entrance into the true Church? Well, this could be the effective agent for constituting the doctrine of papal infallibility as a Catholic dogma.

After all there was no other way of accepting the definition as a dogma consistent with his principles. It would be absurd to take the Pope’s word as a de fide profession of his own infallibility. According to Newman the Roman Pontiff’s infallibility had hitherto been merely a matter of opinion, and one who is only probably infallible can certainly not issue a definitive doctrinal judgment on his own authority. The Council was a broken reed, since, apart from any other consideration, it had never been formally closed. Only the “Securus judicat orbis terrarum” is left, and “This indeed is a broad principle by which all acts of the rulers of the Church are ratified.” “In this passage of my private letter,” Newman later explained, “I meant by ‘ratified’ brought home to us as authentic. At this very moment it is certainly the handy, obvious, and serviceable argument for our accepting the Vatican definition of the Pope’s Infallibility.”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 315-316; italics given.)

Once again, it is staggering to read of such desperate attempts by Newman to avoid at all costs an unqualified acceptance of the definition that he’s willing to cast sound theology aside.

Newman’s original position in the infallibility controversy had been in favor of treating this doctrine as an opinion. It was basically on this point that he lashed out against his opponents before the Council, and it was with this in view that he deplored the attempts at definition within the Council and for a time refused to acknowledge the de fide status of the teaching even after the Council had spoken. Finally, after there could be no doubt concerning the judgment of the great body of the faithful, he found a means for reestablishing the domain of opinion in this field. The instrument that he employed was his beloved doctrine of “minimizing.”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, p. 316)

This “minimism” — clearly also favored by Peter Kwasniewski — was a false view of conciliar teaching noted by Fenton as gaining traction among Catholics in the 1940s (see p. 320). Taken to its most extreme it holds that “the Pope is infallible so long as he defines nothing” — and of course that has been even more notable since the Modernist revolution of Vatican II in the 1960s.

To conclude the section outlining Msgr. Fenton’s article, which we highly recommend be read in its entirety for those with interest on the subject, he brings up the unpleasant dichotomy between the scorn Newman visits upon the reputations of Ultramontanist Council Fathers and the strange affinity he showed for men like Gladstone and Döllinger, who showed contempt towards the Church and the Holy Father:

Newman never loses an opportunity for an expression of bitterness towards a group which included, after all, the leading Prelates of Christendom. He has only expressions of courtesy for the bumbling politician who had ventured to attack the Church of God. He has only expressions of sympathy for those opponents of the definition who had left the Church. His harsh words are reserved for a group that included men like Archbishops Spalding and Manning. … It is characteristic of the relations of the two great English churchmen that, when the then Cardinal Prefect of Propaganda, Cardinal Franchi, wrote to Archbishop Manning on the subject of censurable propositions in the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, Manning hastened to reply begging that no public action be taken against Fr. Newman, and giving as his first and principal reason the assertion that “The heart of the revered Fr. Newman is as right and as Catholic as it is possible to be.’”

(Fenton, “John Henry Newman and the Vatican Definition of Papal Infallibility”, pp. 317-318)

In matters theological — aside from his manifest errors on papal infallibility — Newman may overall be seen to be the greater of the two men, but in terms of public courtesy and conduct, Manning stood far taller, not only as seen above, but when, at the death of Cardinal Newman in 1890, putting aside all memory of the nastiness with which his fellow English churchman had demeaned him during the Council, and preferring to focus on their friendship, Cardinal Manning gave an eloquent eulogy for Newman at the latter’s Requiem Mass, beginning with the words: “We have lost our greatest witness for the Faith, and we are all poorer and lower by the loss.”

Why Vatican I’s Definition of Papal Infallibility was Needed

One of Fr. Newman’s more serious faux pas regarding the Council’s papal infallibility definition — that it was an “inopportune” and unnecessary time for the promulgation — is something that Dr. Kwasniewski regrettably embraces wholeheartedly. The passage of Newman’s that he wants his readers to focus on reads in part:

I have various things to say about the Definition … [T]o me the serious thing is this, that, whereas it has not been usual to pass definition except in case of urgent and definite necessity, this definition, while it gives the Pope power, creates for him, in the very act of doing so, a precedent and a suggestion to use his power without necessity, when ever he will, when not called on to do so. I am telling people who write to me to have confidence—but I don’t know what I shall say to them, if the Pope did so act. And I am afraid moreover, that the tyrant majority is still aiming at enlarging the province of Infallibility.

(John Henry Newman to Ambrose St. John; quoted in Kwasniewski, “My Journey from Ultramontanism to Catholicism”; italics given.)

Of course, none of these dire calamities ever came to fruition, they existed only in Newman’s anti-definition fever dreams. Nonetheless, they are predictions that Kwansniewski ludicrously perpetuates after the fact to drive forward his recognize-and-resist agenda, crassly presuming that his audience will not have the knowledge nor the inclination to research the truth about what happened at Vatican I, and will instead rely on his rather tendentious narration of events.

Did the Council’s dogmatic definition “give the Pope power”? No, of course not — that is yet another place where Newman departs from sound Catholic thought, for the Supreme Pontiff obviously received all his power from the Lord Jesus Christ. All the Council did was formally clarify and confirm what power was bestowed upon all Popes by the Lord Himself when He instituted the Papal Office. Unfortunately, Prof. Kwasniewski has found Newman’s framing to be extremely useful for spinning his version of the recognize-and-resist fable.

In no way were the majority bishops interested in “enlarging the province of Infallibility” — that is simply jaundiced propagandizing on Newman’s part, though it comes in handy for Kwasniewski. In classic “the blind leading the blind” fashion, the professor argues that the Ultramontanists had steered off of the path of true doctrinal development, leading to a permutatio (corruption) of doctrine, constituting a real danger to the Church (here St. Vincent of Lérins is vainly appealed to as a witness against the “tyrant majority”). We’ve already demonstrated that just the opposite was the case: Fr. Toner in The Catholic Encyclopedia laid out an ironclad case for the definition having an organic continuity with earlier magisterial pronouncements, thus showing it to be a genuine profectus (progress), in St. Vincent’s terminology. Newman might have had an ever-so-slight excuse for his error in this regard, but Kwasniewski with the luxury of hindsight has none.

The passage that sums up how Newman defends his reluctance to accept the definition — really a pretext to conceal his insistence that it forever remain in the shadowland of unresolved theological opinion — is that “it has not been usual to pass definition except in case of urgent and definite necessity…”. What he writes after that is a huge leap of logic that doesn’t quite connect with the other side of the canyon, namely, that this will inevitably lead to granting the Pope the impetus “to use his power without necessity”. This simply doesn’t follow.

Regardless, what Newman refused to admit is that there indeed was a very urgent and definite necessity for defining papal infallibility, that being the large-scale attack on the Catholic Church and Christendom from secular, materialistic enemies in politics and culture, such as Chancelor Otto von Bismarck’s Kulturkampf in Germany and the Masonically-aligned Know-Nothings in the United States (see discussion in PART TWO of the present study). Making matters worse were those within the Church who, as we will see, were “boasting of the name of Catholic, and using that name to the ruin of those weak in faith” by arguing in favor of a less than filial devotion and submission to the Apostolic See and its teachings.

To pretend the need wasn’t urgent was to ignore the many warnings sounded by the Holy See in the decades leading up to the Council. These were distilled into Pope Pius IX’s clarion call to action, The Syllabus of Errors (1864), which condemned 80 propositions under ten headings:

1. Pantheism, Naturalism and Absolute Rationalism;

2. Moderate Rationalism;

3. Indifferentism and Latitudinarianism;

4. Socialism, Communism, Secret Societies, Bible Societies and Liberal Clerical societies;

5. Errors concerning the Church and her Rights

6. Errors about Civil Society, considered both in itself and in its relation to the Church;

7. Errors concerning Natural and Christian Ethics;

8. Errors concerning Christian Marriage;

9. Errors regarding the civil power of the Sovereign Pontiff;

10. Errors having reference to Modern Liberalism

In his excellent 1877 book, The True Story of the Vatican Council, the Archbishop of Wesminster, Cardinal Henry Edward Manning (1808-1892), demolishes the empty pretenses of the “inopportunists”. Although his enemies, and some simply ignorant of the facts, labeled him an extreme Ultramontanist, he can be more accurately described as holding a very sensible and enlightened moderate view. A convert from Anglicanism like Newman, Manning (photo left) promoted a wide range of secondary (or indirect) objects that can be defined infallibly by the Pope. (These objects have been enumerated by the Dutch theologian Msgr. Gerard van Noort as consisting of: 1. theological conclusions; 2. dogmatic facts; 3. the general discipline of the Church; 4. approval of religious orders; and 5. canonization of saints.)

In his excellent 1877 book, The True Story of the Vatican Council, the Archbishop of Wesminster, Cardinal Henry Edward Manning (1808-1892), demolishes the empty pretenses of the “inopportunists”. Although his enemies, and some simply ignorant of the facts, labeled him an extreme Ultramontanist, he can be more accurately described as holding a very sensible and enlightened moderate view. A convert from Anglicanism like Newman, Manning (photo left) promoted a wide range of secondary (or indirect) objects that can be defined infallibly by the Pope. (These objects have been enumerated by the Dutch theologian Msgr. Gerard van Noort as consisting of: 1. theological conclusions; 2. dogmatic facts; 3. the general discipline of the Church; 4. approval of religious orders; and 5. canonization of saints.)

As evidence of the need for the Council, Manning cites the Syllabus and proceeds to build considerably, even noting that driving forces behind the Church’s antagonists included “the Gnosticism, illuminism, and intellectual aberrations of the nineteenth century…” (p. 192). He also writes:

The last error condemned in the syllabus is that “the Roman Pontiff can and ought to reconcile himself and come to terms with progress, liberalism, and modern civilisation.” The Christian civilisation represented by the Roman Pontiff consists in the unity of faith, the unity of worship, of Christian marriage and Christian education. No reasonable man can wonder, therefore, if Pius the Ninth declines to reconcile himself with indifferentism in faith and worship, divorce courts, and secular schools.

(Henry Edward Manning, The True Story of the Vatican Council [London: Henry S. King & Co., 1877], p. 30)

Elsewhere, he recounts the concurrence of opinion by the vast majority of bishops to the mind of the Pope on the absolute opportuness of the Council. Because Abp. Manning’s presentation is so potent a corrective to the paucity of the arguments from the other side, to the nonsense arguments of Fr. Newman and other obstructionists/obscurantists in his circle, and the empty head-bobbing acceptance of dedicated 21st-century sycophants of theirs such as Prof. Kwasniewski, it seems fitting to provide still further proof to put an end to the false narrative of there not having been an urgent and definite need for the conciliar definition.

Abp. Manning describes how Pope Pius IX sent a circular letter to 36 European bishops along with certain Oriental bishops (i.e. Eastern-rite Catholic bishops) to assess their interest in the convocation of a council and to see what subjects they would identify as the most important to put on the agenda:

Although the injunction contained in the letters regarded only the matters to be treated, yet the bishops, in their replies, could not refrain from expressing their joy that the Pope had decided to hold an Oecumenical Council. The letters exhibit a wonderful harmony of judgment. They differ, indeed, in the degree of conciseness or diffuseness with which the several subjects are treated; but in the matters suggested for treatment they manifest the unanimity which springs from the unity of the Catholic episcopate.

The bishops note that in our time there exists no new or special heresy in matters of faith, but rather a universal perversion and confusion of first truths and principles which assail the foundations of truth and the preambles of all belief. That is to say, as doubt attacked faith, unbelief has avenged faith by destroying doubt. Men cease to doubt when they disbelieve outright. They have come to deny that the light of nature and the evidences of creation prove the existence of God. They deny, therefore, the existence of God, the existence of the soul, the dictates of conscience, of right and wrong, and of the moral law. If there be no God, there is no legislator, and their morality is independent of any lawgiver, and exists in and by itself, or rather has no existence except subjectively in individuals, by customs inherited from the conventional use and the mental habits of society. They note the wide-spread denial of any supernatural order, and therefore of the existence of faith. They refer to the assertion that science is the only truth which is positive, and to the alleged sufficiency of the human reason for the life and destinies of man, or, in other words, deism, independent morality, secularism, and rationalism, which have invaded every country of the west of Europe. The bishops suggest that the Council should declare that the existence of God may certainly be known by the light of nature, and define the natural and supernatural condition of man, redemption, grace, and the Church. They specially desired the treatment of the nature and personality of God distinct from the world, creation, and providence, the possibility and the fact of a divine revelation. These points may seem strange to many readers, but those who know the philosophies current in Germany and France will at once perceive the wisdom of these suggestions.

They then more explicitly propose for treatment the elevation of man by grace at creation to a superior natural order, the fall of man, his restoration in Christ, the divine institution of the Church, the mission entrusted to it by its Divine Founder, its organization, its endowments and rights, the primacy, and the jurisdiction of the Roman Pontiff; its independence of civil powers, and its relation to them; its authority over education, and the present necessity of the temporal power of the Holy See. These points have been here recited in full in order to show that the one subject for which, we are told, the Council was assembled, was hardly so much as mentioned. Out of thirty-six bishops a few only suggested the infallibility of the head of the Church, though his primacy could not be treated without it.

They are very few (writes one of the bishops) who at this day impugn this prerogative of the Roman Pontiff; and this they do, not in virtue of theological reasons, but with the intention of affirming the liberty of science with greater safety. It seems that with this view a school of theologians has sprung up in Bavaria, at Munich, who in all their writings have principally before them, by the help of historical dissertations, to lower the Apostolic see, its authority, and its mode of government, by throwing contempt upon it, and by attacking, above all, the infallibility of Peter teaching ex cathedra.

With these few exceptions the bishops occupied themselves with Pantheism, Rationalism, Naturalism, Socialism, Communism, indifference in matters of religion, Regalism, the licence of conscience and of the press, civil marriage, spiritism, magnetism, the false theories on inspiration, on the authority of Scripture, and on interpretation. Many of them refer to the syllabus as giving the best outline of matters to be treated, and express the desire that the errors therein condemned should be condemned in the Council….

(Manning, The True Story of the Vatican Council, pp. 25-28)

There is much, much more of value provided by Abp. Manning, further showing how completely out of touch Fr. Newman was with the main current of Catholic thought on the matter. For example, he provides an appendix showing the overwhelming pro-definition sentiment found in official synodal statements starting in the two decades prior to the Vatican Council that included such gatherings as the Provincial Councils held at Cologne, Prague, Colocza (Hungary), and Westminster, the Plenary Council of Baltimore, Italian bishops together with the Order of St. Francis, and a celebration of the 18th centenary of the martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul in Rome (attended by nearly 500 bishops).

To cite one more clincher from The True Story of the Vatican Council, Manning reproduces the petition that the Italian bishops had sent out as part of a query by a Pontifical Commission to determine interest in promulgation of the definition of papal infallibility. The response, again, was overwhelmingly positive, with the inopportunists comprising a cross section so numerically insignificant as to be miniscule, and these few negative responses offering no cogent reason to oppose such a definition.

In Manning’s book, the resulting letter that defends the necessity for the promulgation, and its appendix, stretch out over roughly six pages of small text, beginning at page 115. Below we reproduce only the opening paragraphs and follow them with the link to said pages for those interested in reading the letter in its entirety:

REASONS FOR WHICH THIS DEFINITION IS THOUGHT OPPORTUNE AND NECESSARY

The Sacred Scriptures plainly teach the primacy of jurisdiction of the Roman Pontiff, the successor of St Peter, over the whole Church of Christ, and, therefore, also his primacy of supreme teaching authority.

The universal and constant tradition of the Church, as seen both in facts and in the teaching of the fathers, as well as in the manner of acting and speaking adopted by many Councils, some of which were Oecumenical, teaches us that the judgments of the Roman Pontiff in matters of faith and morals are irreformable.

In the Second Council of Lyons, with the consent of both Greeks and Latins, a profession of faith was agreed upon, which declares: “When controversies in matters of faith arise, they must be settled by the decision of the Roman Pontiff.” Moreover, in the Oecumenical Synod of Florence, it was defined that “the Roman Pontiff is Christ’s true Vicar, the head of the whole Church, and father and teacher of all Christians ; and that to him, in blessed Peter, was given by Jesus Christ the plenitude of power to rule and govern the Universal Church.” Sound reason, too, teaches us that no one can remain in communion of faith with the Catholic Church who is not of one mind with its head, since the Church cannot be separated from its head even in thought.

Yet some have been found, and are even now to be found, who, boasting of the name of Catholic, and using that name to the ruin of those weak in faith, are bold enough to teach that sufficient submission is yielded to the authority of the Roman Pontiff, if we receive his decrees in matters of faith and morals with an obsequious silence, as it is termed, without yielding internal assent, or, at most, with a provisional assent, until the approval or disapproval of the Church has been made known. Anyone can see that by this perverse doctrine the authority of the Roman Pontiff is overturned, all unity of faith dissolved, a wide field open to errors, and time afforded for spreading them far and wide.

Wherefore the bishops, the guardians and protectors of Catholic truth, have endeavoured, especially now-a-days, to defend in their synodal decrees, and by their united testimony, the supreme authority of the Apostolic See.

But the more clearly Catholic truth has been declared, the more vehemently has it been attacked both in books and in newspapers, for the purpose of exciting Catholics against sound doctrine, and preventing the Council of the Vatican from defining it.