Clear ideas on a confusing subject…

Is the Pope an Absolute Monarch?

The Authority of the Roman Pontiff in the Catholic Church

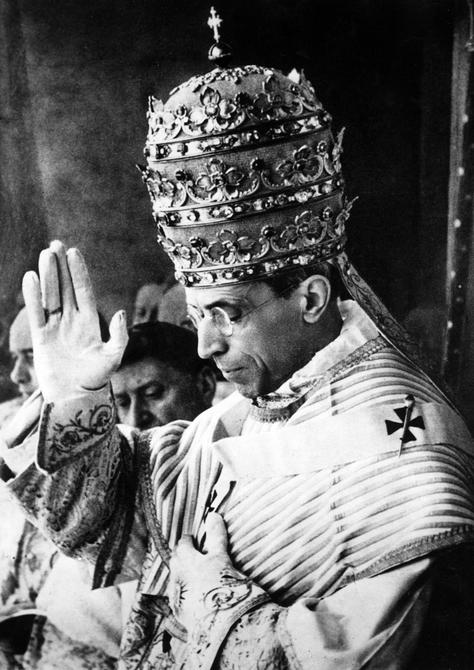

True Vicar of Christ: His Holiness, Pope Pius XII (r. 1939-58)

True Vicar of Christ: His Holiness, Pope Pius XII (r. 1939-58)

(image: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo)

We live in a post-Traditionis Custodes world. It is not surprising, therefore, that it has become more fashionable than ever now for recognize-and-resist traditionalists to try to find all sorts of ways to limit or downplay papal authority, lest they should actually have to submit loyally to the decree their extremely valid “Pope” Francis released this past July 16, which gradually phases out the Traditional Latin Mass.

Not that Francis is actually Pope — it is glaringly obvious that the divine prerogatives Christ has bestowed upon St. Peter and his successors are not verified in the “pontificate” of Jorge Bergoglio. But the recognize-and-resist trads believe him to be, and still they stubbornly refuse to countenance Sedevacantism as the correct diagnosis of the malady that has afflicted the Catholic Church since the death of Pope Pius XII in 1958. As we have lamented on this blog so many times, they prefer denying the doctrine on the Papacy to denying its bogus claimant, thinking that unless the Argentinian apostate be a true Pope, the gates of hell have prevailed — when it is exactly the other way around, of course. Denying the Faith in order to uphold it, now surely that is going to be as successful as trying to borrow one’s way out of debt!

One very popular argument we hear repeated a lot these days is that Catholics can reject from a Pope whatever they think doesn’t conform to Tradition on the grounds that the Pope is not an “absolute monarch” — he simply does not have the authority to “contradict Tradition”. Absolute monarchy, a form of government, is generally understood as “a form of monarchy in which the monarch holds supreme autocratic authority, principally not being restricted by written laws, legislature, or unwritten customs” (Wikipedia).

As “evidence” for the claim that the Pope is not an absolute monarch, the recognize-and-resist traditionalists strangely love to use as their authority the notorious Vatican II Modernist Joseph Ratzinger, better known in our day as “Pope Emeritus” Benedict XVI.

The following two Ratzinger quotes, the first one from his time as head of the Congregation for the Destruction of the Faith (1982-2005), the other from his first few weeks as “Pope”, have been adduced in support of the thesis:

After the Second Vatican Council, the impression arose that the pope really could do anything in liturgical matters, especially if he were acting on the mandate of an ecumenical council. Eventually, the idea of the givenness of the liturgy, the fact that one cannot do with it what one will, faded from the public consciousness of the West. In fact, the First Vatican Council had in no way defined the pope as an absolute monarch. On the contrary, it presented him as the guarantor of obedience to the revealed Word. The pope’s authority is bound to the Tradition of faith, and that also applies to the liturgy. It is not “manufactured” by the authorities. Even the pope can only be a humble servant of its lawful development and abiding integrity and identity…. The authority of the pope is not unlimited; it is at the service of Sacred Tradition.

(“Cardinal” Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy [San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2000], p. 166)

The power that Christ conferred upon Peter and his Successors is, in an absolute sense, a mandate to serve. The power of teaching in the Church involves a commitment to the service of obedience to the faith. The Pope is not an absolute monarch whose thoughts and desires are law. On the contrary: the Pope’s ministry is a guarantee of obedience to Christ and to his Word. He must not proclaim his own ideas, but rather constantly bind himself and the Church to obedience to God’s Word, in the face of every attempt to adapt it or water it down, and every form of opportunism.

…The Pope knows that in his important decisions, he is bound to the great community of faith of all times, to the binding interpretations that have developed throughout the Church’s pilgrimage. Thus, his power is not being above, but at the service of, the Word of God. It is incumbent upon him to ensure that this Word continues to be present in its greatness and to resound in its purity, so that it is not torn to pieces by continuous changes in usage.

(Antipope Benedict XVI, Homily at St. John Lateran, May 7, 2005)

The one or the other, or both, of these two quotations have been used by some of the most well-known recognize-and-resist apologists as an argument in defense of their theological position that refuses submission to the putative Roman Pontiff whenever they deem it “necessary” to keep the Church from — putting it bluntly — going to hell.

For example, “Bp.” Athanasius Schneider has made this argument. “Fr.” Nicholas Gruner used it (see p. 2 here). Christopher Ferrara has used it again and again on The Remnant web site and in his book The Great Facade (on p. 146 of the original 2002 edition and on p. 118 of the 2015 edition). The Rorate Caeli blog happily used it in 2015. And of course Dr. Peter Kwasniewski has been busy recycling this quote as well (here in 2014 in a letter to Novus Ordo apologist Dave Armstrong; and just the other day in a lecture that was published on Rorate Caeli).

It’s too bad that a few years back, the same Rorate Caeli published a post by historian Roberto de Mattei lamenting: “The Church is preparing to become a Republic, not a presidential one but a parliamentary one, wherein the Head of State has a mere role as guarantor of the political parties and the representative of national unity, renouncing the mission of absolute monarch and supreme legislator as the Roman Pontiff” (underlining added). Well, at least they’re all in agreement that the Vatican II Church denies that the Pope is an absolute monarch. Now if only they could make up their minds about whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing!

Ratzinger’s words can probably be understood in an orthodox sense, although we will not go so far as to assume that Ratzinger meant them in an orthodox sense — or that the recognize-and-resisters are understanding them in that way. We will return to that issue later.

The first question we must ask is: Why do these “traditionalists” — we call them “semi-traditionalists” for a reason — resort to quoting a Modernist as an authority on the Papacy in the first place? Why didn’t they quote Pope Pius IX, for instance? Why do they feel the need to rely on Joseph Ratzinger, whom Christopher Ferrara once aptly described as “perhaps the most industrious ecclesial termite of the post-conciliar epoch, tearing down even as he makes busy with the appearance of building up”?

That this is the same Ratzinger who also denies the dogma of papal primacy in his 1982 book Theologische Prinzipienlehre (released in English as Principles of Catholic Theology in 1987), seems of no concern to them — or are they not aware of it? If not, we’re happy to help out (please forgive the long quotation, but we need to provide a generous excerpt here, lest we be accused of taking him out of context):

The maximum demands on which the search for unity [between Catholics and Eastern Orthodox] must certainly founder are immediately clear. On the part of the West, the maximum demand would be that the East recognize the primacy of the bishop of Rome in the full scope of the definition of 1870 and in so doing submit in practice, to a primacy such as been accepted by the Uniate churches. On the part of the East, the maximum demand would be that the West declare the 1870 doctrine of primacy erroneous and in so doing submit, in practice, to a primacy such as been accepted with the removal of the Filioque from the Creed and including the Marian dogmas of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As regards Protestantism, the maximum demand of the Catholic Church would be that the Protestant ecclesiological ministries be regarded as totally invalid and that Protestants be converted to Catholicism; the maximum demand of Protestants, on the other hand, would be that the Catholic Church accept, along with the unconditional acknowledgment of all Protestant ministries, the Protestant concept of ministry and their understanding of the Church and thus, in practice, renounce the apostolic and sacramental structure of the Church, which would mean, in practice, the conversion of Catholics to Protestantism and their acceptance of a multiplicity of distinct community structures as the historical form of the Church. …

…[N]one of the maximum solutions offers any real hope of unity. In any event, church unity is not a political problem that can be solved by means of compromise or the weighing of what is regarded as possible or acceptable. What is at stake here is unity of belief, that is, the question of truth, which cannot be the object of political maneuvering. As long as and to the extent that the maximum solution must be regarded as a requirement of truth itself, just so long and to just that extent will there be no other recourse than simply to strive to convert one’s partner in the debate. In other words, the claim of truth ought not to be raised where there is not a compelling and indisputable reason for doing so. We may not interpret as truth that which is, in reality, a historical development with a more or less close relationship to truth. …

…Certainly, no one who claims allegiance to Catholic theology can simply declare the doctrine of primacy null and void, especially not if he seeks to understand the objections and evaluates with an open mind the relative weight of what can be determined historically. Nor is it possible, on the other hand, for him to regard as the only possible form and, consequently, as binding on all Christians the form this primacy has taken in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The symbolic gestures of Pope Paul VI and, in particular, his kneeling before the representative of the Ecumenical Patriarch [the schismatic Patriarch Athenagoras I] were an attempt to express precisely this and, by such signs, to point the way out of the historical impasse. …

…Rome must not require more from the East with respect to the doctrine of primacy than had been formulated and was lived in the first millennium. When the [heretical-schismatic] Patriarch Athenagoras, on July 25, 1967, on the occasion of the Pope’s visit to Phanar, designated him as the successor of St. Peter, as the most esteemed among us, as one who presides in charity, this great Church leader was expressing the essential content of the doctrine of primacy as it was known in the first millennium. Rome need not ask for more. Reunion could take place in this context if, on the one hand, the East would cease to oppose as heretical the developments that took place in the West in the second millennium and would accept the Catholic Church as legitimate and orthodox in the form she had acquired in the course of that development, while, on the other hand, the West would recognize the Church of the East as orthodox and legitimate in the form she has always had.

…

Patriarch Athenagoras himself spoke … strongly when he greeted the Pope in Phanar: “Against all expectation, the bishop of Rome is among us, the first among us in honor, ‘he who presides in love’ (Ignatius of Antioch, epistola “Ad Romano”, PG 5, col. 801, prologue).” It is clear that, in saying this, the Patriarch did not abandon the claims of the Eastern Churches or acknowledge the primacy of the West. Rather, he stated plainly what the East understood as the order, the rank and title, of the equal bishops in the Church — and it would be worth our while to consider whether this archaic confession, which has nothing to do with the “primacy of jurisdiction” [defined at Vatican I] but confesses a primacy of “honor” (τιμή) and agape [love], might not be recognized as a formula that adequately reflects the position Rome occupies in the Church — “holy courage” requires that prudence be combined with “audacity”: “The kingdom of God suffers violence” [cf. Mt 11:12].

(Joseph Ratzinger, Principles of Catholic Theology: Building Stones for a Fundamental Theology, trans. by Sister Mary Frances McCarthy, S.N.D. [San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1987], pp. 197-199, 217; underlining added.)

What Ratzinger wrote there is a clear and direct denial of the Catholic dogma of papal primacy as defined at the First Vatican Council of 1870, as will be shown below. And that means that if there is one man a traditional Catholic should not be citing as any kind of theological authority on the nature and limits of the Papacy, the old Modernist Ratzinger would be it.

We have every right to ask, therefore: Instead of relying on a manifest non-Catholic like Ratzinger, why don’t the semi-trads look for the traditional Catholic teaching on this?

Pope St. Pius X taught quite candidly that the Catholic Church is “a sovereignty of one person, that is a monarchy” (Apostolic Letter Ex Quo; Denz. 2147a). Although the term “absolute” is not used, it is Catholic dogma that the Pope enjoys full, supreme, and immediate authority over all the faithful in spiritual matters (not only in doctrine but also in discipline). To deny this is heresy:

If anyone thus speaks, that the Roman Pontiff has only the office of inspection or direction, but not the full and supreme power of jurisdiction over the universal Church, not only in things which pertain to faith and morals, but also in those which pertain to the discipline and government of the Church spread over the whole world; or, that he possesses only the more important parts, but not the whole plenitude of this supreme power; or that this power of his is not ordinary and immediate, or over the churches altogether and individually, and over the pastors and the faithful altogether and individually: let him be anathema.

(First Vatican Council, Dogmatic Constitution Pastor Aeternus, Chapter 3; Denz. 1831.)

The Pope of Vatican I, Pius IX, also taught the following:

Nor can we pass over in silence the audacity of those who, not enduring sound doctrine, contend that “without sin and without any sacrifice of the Catholic profession assent and obedience may be refused to those judgments and decrees of the Apostolic See, whose object is declared to concern the Church’s general good and her rights and discipline, so only it does not touch the dogmata of faith and morals.” But no one can be found not clearly and distinctly to see and understand how grievously this is opposed to the Catholic dogma of the full power given from God by Christ our Lord Himself to the Roman Pontiff of feeding, ruling and guiding the Universal Church.

(Pope Pius IX, Encyclical Quanta Cura, n. 5)

What good is it to proclaim aloud the dogma of the supremacy of St. Peter and his successors? What good is it to repeat over and over declarations of faith in the Catholic Church and of obedience to the Apostolic See when actions give the lie to these fine words? Moreover, is not rebellion rendered all the more inexcusable by the fact that obedience is recognized as a duty? Again, does not the authority of the Holy See extend, as a sanction, to the measures which We have been obliged to take, or is it enough to be in communion of faith with this See without adding the submission of obedience, — a thing which cannot be maintained without damaging the Catholic Faith?

…In fact, Venerable Brothers and beloved Sons, it is a question of recognizing the power (of this See), even over your churches, not merely in what pertains to faith, but also in what concerns discipline. He who would deny this is a heretic; he who recognizes this and obstinately refuses to obey is worthy of anathema.

(Pope Pius IX, Encyclical Quae in Patriarchatu [Sept. 1, 1876], nn. 23-24; in Acta Sanctae Sedis X [1877], pp. 3-37; English taken from Papal Teachings: The Church, nn. 433-434.)

In 1870, just before Vatican I promulgated its dogmatic constitution defining the infallibility of the Roman Pontiff, the celebrated abbot Dom Prosper Gueranger (1805-1875) published a book defending the “Ultramontanist” (that is, orthodox) understanding of the Papacy in direct reply to the Gallican errors of Bishop Henri Maret (1805-1884), who had written a book under the pseudonym “Bishop de Sura”. In English translation, Dom Gueranger’s work bears the apt title The Papal Monarchy. Pope Pius IX was so pleased with it that he personally endorsed the book in a letter to the author dated Mar. 12, 1870.

All of this is relevant to our discussion because one of Bishop de Sura’s objections was that the “Ultramontanist” view made the Pope into an “absolute monarch”, and surely that would be a distortion of his true role. Although Abbot Gueranger did not adopt the term himself, he did not reject or deny it either. He simply responded:

Bishop de Sura can protest as much as he wants against what he calls the absolute monarchy of the pope; the Council of Florence has defined, as a doctrine to be held by [divine] faith, that the pope possesses the full power to govern the entire Church; this word shall not pass away [cf. Mark 13:31].

(Dom Prosper Gueranger, The Papal Monarchy [Fitzwilliam, NH: Loreto Publications, 2007], p. 68; italics given.)

At the end of the day, it does not so much matter what precise label we give to the form of ecclesiastical government that is the Papacy. The Catholic Church is a divine institution; Christ founded her unchangeably with a form of government in which the Pope has full and supreme jurisdiction over every Catholic with regard to matters of Faith and morals. If we have to compare it to a human form of government, it would most probably resemble an absolute monarchy most closely.

This, indeed, is what the Doctor of the Church St. Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) says in response to the French theologian Jean Gerson (1363-1429):

The Holy Church is not like the Republic of Venice, or of Genoa, or of some other city … [where] it can be said that the Republic is above the Prince. Nor is it like a worldly kingdom in which the people transfers its own authority to the monarch … For the Church of Christ is a most perfect kingdom and an absolute monarchy which neither depends on the people nor has from it its origin, but depends on the divine will alone.

(St. Robert Bellarmine, Risposta di Card. Bellarmino, ad un libretto intitulato Trattato, e resolutione, sopra la validità de la scommuniche die Geo. Gersono; in Risposta del Card. Bellarmino a due Libretti [Rome, 1606], pp. 75-76. Translation taken from Francis Oakely, The Conciliarist Tradition [New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003], p. 218; underlining added.)

This absolute monarchy that is the Catholic Church has as her invisible Head the Lord Jesus Christ; and her visible head is His Vicar, the Pope of Rome:

But we must not think that [Christ] rules [His Church] only in a hidden or extraordinary manner. On the contrary, our Divine Redeemer also governs His Mystical Body in a visible and normal way through His Vicar on earth. You know, Venerable Brethren, that after He had ruled the “little flock” [Lk 12:32] Himself during His mortal pilgrimage, Christ our Lord, when about to leave this world and return to the Father, entrusted to the Chief of the Apostles the visible government of the entire community He had founded. Since He was all wise He could not leave the body of the Church He had founded as a human society without a visible head. Nor against this may one argue that the primacy of jurisdiction established in the Church gives such a Mystical Body two heads. For Peter in virtue of his primacy is only Christ’s Vicar; so that there is only one chief Head of this Body, namely Christ, who never ceases Himself to guide the Church invisible, though at the same time He rules it visibly, through him who is His representative on earth. After His glorious Ascension into heaven this Church rested not on Him alone, but on Peter too, its visible foundation stone.

(Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Mystici Corporis, n. 40)

Being the Vicar of Christ, the Pope has full and supreme jurisdiction over the entire Church. One may say that within those parameters established by God for His Church, the Pope’s authority is absolute.

The 18th-century Doctor of the Church St. Alphonsus Liguori (1696-1787), for instance, referred to the Roman Pontiff’s authority as “absolute”. Fr. David Sharrock explains that the saint’s “aim was to prove that this man who is Christ’s Vicar upon earth, is vested by Christ with supreme and absolute authority over everyone in Christ’s Mystical Body; and that only if this supreme and absolute authority is recognized and accepted by all, can Christ’s Church live and progress” (The Theological Defense of Papal Power by St. Alphonsus de Liguori [Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1961], p. 89; underlining added).

Nevertheless, the papal monarchy is not absolute in the sense of being able to change the divine constitution of the Church. After all, the Pope is not God, He is only His Vicar and therefore has no power to change how Christ set up the Church. As the Church is “by divine will and constitution, such it must uniformly remain to the end of time” (Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical Satis Cognitum, n. 3).

Now our Blessed Lord instituted not merely the office of Pope but also the office of bishop. Therefore, although the Pope has supreme authority, it would not be within his power to abolish the episcopacy:

But if the authority of Peter and his successors is plenary and supreme, it is not to be regarded as the sole authority. For He who made Peter the foundation of the Church also “chose, twelve, whom He called apostles” (Luke vi., 13); and just as it is necessary that the authority of Peter should be perpetuated in the Roman Pontiff, so, by the fact that the bishops succeed the Apostles, they inherit their ordinary power, and thus the episcopal order necessarily belongs to the essential constitution of the Church. Although they do not receive plenary, or universal, or supreme authority, they are not to be looked as vicars of the Roman Pontiffs; because they exercise a power really their own, and are most truly called the ordinary pastors of the peoples over whom they rule.

(Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical Satis Cognitum, n. 14)

In his famous De Romano Pontifice (“On the Roman Pontiff”), St. Robert Bellarmine had explained the same thing drawing an analogy with the human forms of government:

…[T]he absolute and free king of the whole Church is Christ alone…. Therefore, an absolute and free monarch is not sought in the Church, or an aristocracy, or democracy….

For a long time Catholic teachers have all agreed on the point, that the ecclesiastical government which was consigned to men by God is indeed a monarchy, but tempered, as we said above, by aristocracy and democracy.

(St. Robert Bellarmine, On the Roman Pontiff, Book I, Chapter 5; Grant translation, pp. 30-31.)

What does Bellarmine mean by “tempered, as we said above, by aristocracy and democracy”? He means that, by God’s design, the Pope is not the sole ruler of the Church but is assisted in governing the Church by bishops who have true jurisdiction over their flocks, just as Pope Leo XIII taught.

At the same time, the bishops do not govern their dioceses independently of the Roman Pontiff. They must maintain communion with him, submit to his laws and directives, and accept his teachings. This St. Robert explains in Chapter 3 of the same work, to which his words “as we said above” are a reference:

The next proposition is such: government tempered from all three forms on account of the corruption of human nature is more advantageous than simple monarchy. Such a government rightly requires that there should be some supreme prince in the state, who commands all, and is subject to none. Nevertheless, there should be guardians of provinces or cities, who are not vicars of the king or annual judges, but true princes, who also obey the command of the supreme prince and meanwhile govern their province, or city, not as someone else’s property, but as their own. Thus, there should be a place in the commonwealth both for a certain royal monarchy and also an aristocracy of the best princes.

What if we were to add to these that neither the supreme king nor the lesser princes would acquire those dignities in hereditary succession, rather the aristocrats would be carried to those dignities from the whole people; then Democracy would have its attributed place in the state. That this is the best, and in this mortal life the most expedient form of rule, we shall prove from two arguments.

First, a government of this sort should have all those goods, which above we showed are present in monarchy, and should be on that account in this life more favorable and useful. And indeed, it is plain that the goods of monarchy are present in this our government, since this government truly and properly embraces some element of monarchy: it can be observed that this [government] is going to be more favorable in all things, however, because of this very fact, that all love that kind of government more in which they can be partakers; without a doubt this our [form of government] is such, although this is not conveyed by any kind of virtue.

We will speak nothing on the advantage, however, since it may be certain that one individual man cannot rule each individual province and city by himself; whether he might wish or not, he would be compelled for the sake of their care to demand it from his vicars of administration, or from his own princes of these places. Again, it is equally certain, that princes are much more diligent and faithful for their own things than governing vicars for someone else’s.

Another argument is added from divine authority. God established a rule of this sort, such as we have just described, in the Church both in the Old and New Testaments. Furthermore, this can be proved from the Old Testament quite easily: The Hebrews always had one, or ten, or a judge, or a king, who commanded the whole multitude and many lesser princes, about which we read in the book of Exodus: “With vigorous men being chosen from all Israel, he established them princes of the people, tribunes and centurions, both captains of fifty, and of ten, who judged the people at all times” [Ex 18:25-26]. Also, one can see in the first Chapter of the book of Deuteronomy, there is clearly democracy in some manner.

On the Church of the new Testament the same thing will need to be proven, as evidently there is monarchy in the person of the Supreme Pontiff, and also in that of the bishops (who are true princes and shepherds, not merely vicars of the supreme pontiff), there is aristocracy and at length, there is a certain measure of democracy, since there is no man from the whole multitude of Christians who could not be called to the episcopacy, provided he is judged worthy for that office.

(Bellarmine, On the Roman Pontiff, Book I, Chapter 3; Grant translation, pp. 26-27.)

Whether we choose to apply the term “absolute monarch” to the Pope or not, it is important to understand what the true doctrine regarding the Papacy is, and it is that which must be conveyed.

Expounding the dogma of papal primacy as defined at the First Vatican Council, the Dutch theologian Mgr. Gerard van Noort explains that not only is the Pope’s jurisdiction real, universal, ordinary, direct, episcopal, and supreme — it is also “absolutely complete in itself”:

The supreme pontiff possesses in himself alone the plenitude of supreme power, and not merely the major portion of that power. …As a matter of fact…, the supreme pontiff, alone and without the consent of the bishops or of the Church, can do anything that pertains to the jurisdictional powers of the Church.

(Monsignor G. van Noort, Dogmatic Theology II: Christ’s Church [Westminster, MD: The Newman Press, 1957], n. 170, pp. 281-282; italics given.)

It is clear, then, that the Pope is the visible-earthly monarch in the absolute monarchy that is the Church of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Roman Catholic Church; and he has absolutely complete jurisdiction, not only over every bishop but also over every single Catholic. That is the infallible dogmatic teaching of the Vatican Council.

That Vatican I does not give the Pope the power to change the Faith (such as declaring the Ascension of Christ to be untrue) or any Divine Law (such as changing the Ten Commandments), is confirmed by Pope Pius IX himself. To allay the fears of German chancellor Otto von Bismarck over the council’s dogmatic proclamations, and to refute the false accusations he had made in public, the Catholic bishops of Germany — back then there actually were some — explained what the correct understanding of Vatican I’s constitution Pastor Aeternus is, and they explicitly disavowed the term “absolute monarch”:

…[T]he application of the term “absolute monarch” to the pope in reference to ecclesiastical affairs is not correct because he is subject to divine laws and is bound by the directives given by Christ for his Church. The pope cannot change the constitution given to the Church by her divine Founder, as an earthly ruler can change the constitution of a State. In all essential points the constitution of the Church is based on divine directives, and therefore it is not subject to human arbitrariness.

(Common Declaration of German Bishops, Jan./Feb. 1875; Denzinger-Hünermann 3114; English translation from here.)

To prevent Bismarck from dismissing this explanation as not being in conformity with the intentions and thinking of the Pope, Pius IX himself approved it in an Apostolic Letter, writing to the bishops: “…your declaration presents the truly Catholic understanding, which is that of the holy council of this Holy See” (Apostolic Letter Mirabilis Illa Constantia; Denz.-H. 3117).

We have thus clarified the authority the Pope has over the Church. Within the confines established by God Himself, the Pope has power over everything and everyone in the Roman Catholic Church.

As for the objection that this would allow the Pope to pretty much do whatever he wants and thus surely lead the Church to ruin, Mgr. van Noort clarifies:

Finally, from the doctrine outlined above, one should not leap to the absurd conclusion that all things are licit to the pope; or that he may turn things topsy-turvy in the Church at mere whim. Possession of power is one thing; a rightful use of power quite another. The supreme pontiff has received his power for the sake of building up the Church, not tearing it down. In exercising his supreme power he is, by divine law, strictly bound by the laws of justice, equity, and prudence. These laws require that unless necessary or great utility urge the contrary, the pope should, for example, respect the legitimate customs obtaining in various places, observe prescribed ecclesiastical laws, etc. These laws, even though they do not possess a binding power for the pope, do nonetheless normally have for him a directive power. They also demand that in normal circumstances the pope should leave the full running of dioceses to their individual bishops in accord with the advice given by St. Bernard to Pope Eugenius III….

(Van Noort, Dogmatic Theology II: Christ’s Church, n. 171, p. 283)

In other words, although the Pope has the power to do “anything that pertains to the jurisdictional powers of the Church”, that does not mean he is permitted (by Divine Law) to exercise it as he pleases, with no regard for justice, prudence, etc. It is conceivable, therefore, that a Pope could sin by exercising his primacy a certain way, and there is no question that this has happened in the past.

However, although a Pope may be personally guilty of sin (for example, a sin against prudence) for having issued a particular legal decree (for example, abolishing the Jesuit order, as happened in 1773), it does not follow that the decree is therefore void or that it need not be accepted and obeyed by the faithful. Sinful though it may be for the Roman Pontiff to render a particular decision, the decision has legal validity inasmuch as it comes from the lawful authority and inasmuch as it does not command the individuals to whom it is addressed to commit a sin.

Semi-trad apologists will often justify refusal of submission to a (putatively) papal teaching or law by appealing to the moral obligation of disobeying sinful commands: “We ought to obey God, rather than men” (Acts 5:29). But personal sinful commands are one thing; the papal magisterium and the Church’s disciplinary and liturgical laws are something else altogether — they enjoy special divine protection:

Certainly the loving Mother [the Church] is spotless in the Sacraments, by which she gives birth to and nourishes her children; in the faith which she has always preserved inviolate; in her sacred laws imposed on all; in the evangelical counsels which she recommends; in those heavenly gifts and extraordinary graces through which, with inexhaustible fecundity, she generates hosts of martyrs, virgins and confessors.

(Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Mystici Corporis, n. 66; underlining added.)

…[T]he discipline sanctioned by the Church must never be rejected or be branded as contrary to certain principles of natural law. It must never be called crippled, or imperfect or subject to civil authority. In this discipline the administration of sacred rites, standards of morality, and the reckoning of the rights of the Church and her ministers are embraced.

(Pope Gregory XVI, Encyclical Mirari Vos, n. 9)

…as if the Church which is ruled by the Spirit of God could have established discipline which is not only useless and burdensome for Christian liberty to endure, but which is even dangerous and harmful and leading to superstition and materialism.

(Pope Pius VI, Bull Auctorem Fidei, n. 78; Denz. 1578)

Recognize-and-resist pundits think that a true Pope can decree all kinds of evil, pernicious, heretical, and impious things, and when that happens the faithful must manfully resist since they are not allowed to obey what is sinful. The following posts refute that argument:

- St. Robert Bellarmine’s Teaching on Resisting a Pope

- Faith and Authority: When is Disobedience Legitimate?

In consideration of the fact then that, properly understood, the Pope has supreme, complete, and absolute authority over the entire Church, not merely in matters of doctrine but also of ecclesiastical discipline and the Sacred Liturgy (see Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Mediator Dei, n. 58), and considering that only sinful commands can be disobeyed, not ecclesiastical laws or papal teachings, one may wonder who or what could prevent an egregious abuse of such wide-ranging papal power. We can confidently answer that it is God Himself, the Pope’s only Superior:

It is possible, of course, as in all affairs governed by men, for abuses to creep in and for aberrations to occur; but the Divine Bridegroom of the Church, who has promised that the Holy Spirit will be with the Church forever, will always see to it that the Church herself is not exposed to catastrophe by the weakness or imprudence of individual men. One final point remains to be mentioned: the Roman pontiff is subject to no one on earth and consequently cannot be called to judgment by anyone. He is obliged to render an account for his decisions to no one but Him alone whose visible vicar he is, Jesus Christ.

(Van Noort, Dogmatic Theology II: Christ’s Church, n. 171, pp. 283-284)

Indeed this is not merely the pious thinking of one theologian (Mgr. van Noort) — it is the magisterial teaching of the Popes themselves:

…[N]otwithstanding the wiles and intrigues which [the gates of hell] bring to bear against the Church, it can never be that the church committed to the care of Peter shall succumb or in any wise fail. …God confided His Church to Peter so that he might safely guard it with his unconquerable power. He invested him, therefore, with the needful authority; since the right to rule is absolutely required by him who has to guard human society really and effectively….

(Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical Satis Cognitum, n. 12)

…[T]he Church has received from on high a promise which guarantees her against every human weakness. What does it matter that the helm of the symbolic barque has been entrusted to feeble hands, when the Divine Pilot stands on the bridge, where, though invisible, He is watching and ruling? Blessed be the strength of his arm and the multitude of his mercies!

(Pope Leo XIII, Allocution to Cardinals, March 20, 1900; excerpted in Papal Teachings: The Church, p. 349.)

The Pope has the divine promises; even in his human weaknesses, he is invincible and unshakable; he is the messenger of truth and justice, the principle of the unity of the Church; his voice denounces errors, idolatries, superstitions; he condemns iniquities; he makes charity and virtue loved.

(Pope Pius XII, Address Ancora Una Volta, Feb. 20, 1949)

God Himself has set the parameters for the Pope’s authority, and He himself guarantees that certain bounds will never be overstepped. After all, it is His Church — He set it up, He guides it, and He is ultimately in charge of this “glorious church, not having spot or wrinkle, or any such thing” (Eph 5:27); this beautiful “church of the living God, which is the pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15), against which “the gates of hell shall not prevail” (Mt 16:18).

That is why the First Vatican Council also teaches the following:

For, the Holy Spirit was not promised to the successors of Peter that by His revelation they might disclose new doctrine, but that by His help they might guard sacredly the revelation transmitted through the apostles and the deposit of faith, and might faithfully set it forth. Indeed, all the venerable fathers have embraced their apostolic doctrine, and the holy orthodox Doctors have venerated and followed it, knowing full well that the See of St. Peter always remains unimpaired by any error, according to the divine promise of our Lord the Savior made to the chief of His disciples: “I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not: and thou, being once converted, confirm thy brethren” [Luke 22:32].

(Vatican I, Dogmatic Constitution Pastor Aeternus, Chapter 4; Denz. 1836.)

Evidently, what Vatican I is teaching here is that because he is assisted by the Holy Ghost, the Pope will “guard sacredly the revelation transmitted through the apostles and the deposit of faith” and will not “disclose new doctrine” by the revelation of the same Holy Ghost. That is how we can be sure “that the See of St. Peter always remains unimpaired by any error.”

The semi-traditionalists, on the other hand, reduce this beautiful and consoling conciliar teaching to little more than a superficial banality: They act as though it simply means that the Pope isn’t supposed to make new doctrines, for that is not why the Holy Ghost was given him. Such an interpretation of the text is not tenable, however, because that much is true of anyone, not just of the Pope alone. In fact, any Protestant would agree that his own parish pastor isn’t supposed to teach strange new doctrines. That’s hardly a profound insight to be taught by a Catholic ecumenical council about the Pope!

Secondly, notice that the council’s document says that “the Holy Spirit was not promised to the successors of Peter that by His revelation they might disclose new doctrine…” (italics added). If the semi-trads’ understanding of this passage were correct, it would mean that the Pope is not supposed to proclaim new doctrines that are nevertheless revealed to him by the Holy Ghost — a grotesque thing for a Catholic ecumenical council to teach.

Thirdly, the surrounding context given in Chapter 4 of the conciliar constitution Pastor Aeternus establishes the prerogatives and uniqueness of the Papacy, protected by the Holy Ghost. What sort of divine protection would the Holy Ghost provide if the Pope were merely “not supposed to” invent new doctrines but would nevertheless be quite capable of doing so? Wouldn’t that be true also of your local grocery store clerk and the grumpy bus driver on your morning commute? Aren’t they, too, “not supposed to” come up with a new gospel but quite capable of doing precisely that?

It is manifest, therefore, that Vatican I teaches, not that the Pope ought not to teach new (or false) doctrine, but that he actually does not. That is the significance of the special assistance of the Holy Ghost for the Pope. To use more technical terminology, we can say that the council’s doctrine about the Holy Ghost’s assistance for the Pope is descriptive — it describes a truth about the Papacy — and not merely normative — establishing a norm the Pope is expected to follow. The Holy Ghost acts a priori — before the Pope does anything, by preventing him from teaching or legislating grave errors such as heresy — not a posteriori, by means of the Pope’s inferiors correcting his magisterium after the fact.

By the way, treating dogmas as merely normative and not descriptive is actually an error characteristic of Modernism, one explicitly singled out and condemned by Pope St. Pius X in his Syllabus of Modernist Errors: “The dogmas of the Faith are to be held only according to their practical sense; that is to say, as preceptive norms of conduct and not as norms of believing” (Pius X, Decree Lamentabili Sane Exitu, error n. 26). This statement is to “be held by all as condemned and proscribed”, Pope Pius X decreed.

Even Joseph Ratzinger, of all people, agrees with the descriptive understanding of Vatican I when he says, as quoted above, that “the Pope’s ministry is a guarantee of obedience to Christ and to his Word” (Homily at St. John Lateran, May 7, 2005; underlining added).

In short, then, we can summarize this teaching as follows: Whether he be malicious, inept, or just careless, the Pope cannot ruin the Church because God will not allow it. The Pope would drop dead before he could put his signature on a magisterial document that teaches heresy, before he could abolish the episcopacy, or before he could invalidate the sacraments.

By contrast, the recognize-and-resist traditionalists believe that all this is entirely possible, but when it happens, the rest of the Church must rise up to the defy the Roman Pontiff and in some fashion or another get him to change course — a truly bizarre way to understand the Holy Ghost’s protection of the Church! Not only is this without any kind of doctrinal foundation, it undermines the dogma of papal primacy, it makes a mockery of the Church’s divine protection, and it is unworkable in practice.

Not only would the Papacy be pointless, it would actually constitute an immense danger to souls if the Pope were capable, for example, of teaching the foulest doctrinal errors or of instituting a harmful, blasphemous, sacrilegious rite of Mass. Besides, how could the faithful be expected to know they are being misled? Would they have to be more knowledgeable about Catholicism than the Pope? Would they have to trust some lesser cleric more than the Pope? Would they have to look to other individuals — perhaps Carlo Maria Viganò, Athanasius Schneider, Michael Voris, or Peter Kwasniewski — to teach the true, orthodox doctrine? And how could the faithful have assurance that those individuals are so orthodox? How could they be orthodox if they are not with the “Supreme Pastor the Roman Pontiff, who is himself guided by Jesus Christ Our Lord” (Pope Pius XI, Encyclical Casti Connubii, n. 104)? And even if such special individuals are guaranteed to be orthodox when the Pope isn’t, then why not simply dump the Pope altogether and follow those characters instead?

It is easy to see how the Papacy quickly disintegrates into irrelevance and meaninglessness as soon as one tries to fit it into the recognize-and-resist framework. Hence St. Robert Bellarmine teaches:

The Pope is the Teacher and Shepherd of the whole Church, thus, the whole Church is so bound to hear and follow him that if he would err, the whole Church would err.

Now our adversaries respond that the Church ought to hear him so long as he teaches correctly, for God must be heard more than men.

On the other hand, who will judge whether the Pope has taught rightly or not? For it is not for the sheep to judge whether the shepherd wanders off, not even and especially in those matters which are truly doubtful. Nor do Christian sheep have any greater judge or teacher to whom they might have recourse. As we showed above, from the whole Church one can appeal to the Pope yet, from him no one is able to appeal; therefore necessarily the whole Church will err if the Pontiff would err.

(St. Robert Bellarmine, On the Roman Pontiff, Book IV, Chapter 3; Grant translation, p. 160.)

With this in mind, we can now recognize what has been Satan’s masterstroke in his ongoing efforts to deceive the elect (cf. Mt 24:24): Unable to make Christ’s Vicar mislead the Church through false doctrine, blasphemous liturgy, or harmful disciplinary law, the devil found a way to have a series of conclaves produce a number of antipopes, that is, false popes — impostors, charlatans, counterfeits — who, precisely because they are not true Popes, are deprived of the divine protections and guarantees for the Papacy.

Thus the devil has “free rein”, so to speak, to wreak havoc on the Mystical Body of Christ for a certain period of time, just as God allowed him to apparently defeat the Physical Body of Christ two millennia ago. In this way the Church follows her Divine Head in His Passion, as taught by St. Paul, “who now rejoice in my sufferings for you, and fill up those things that are wanting of the sufferings of Christ, in my flesh, for his body, which is the church” (Col 1:24).

All this, we must always remember, is permitted by God for the sake of His elect and to increase His glory: “Ought not Christ to have suffered these things, and so to enter into his glory?” (Lk 24:26). The devil only has power against the Church because God has permitted it: “I lay down my life, that I may take it again. No man taketh it away from me: but I lay it down of myself, and I have power to lay it down: and I have power to take it up again” (Jn 10:17-18). “For the mystery of iniquity already worketh; only that he who now holdeth, do hold, until he be taken out of the way. And then that wicked one shall be revealed whom the Lord Jesus shall kill with the spirit of his mouth; and shall destroy with the brightness of his coming, him, whose coming is according to the working of Satan, in all power, and signs, and lying wonders, and in all seduction of iniquity to them that perish; because they receive not the love of the truth, that they might be saved. Therefore God shall send them the operation of error, to believe lying: that all may be judged who have not believed the truth, but have consented to iniquity” (2 Thess 2:7-11).

It is not hard to see that this “operation of error” is in full swing in our day. Tragically, by distorting the true Catholic teaching on the Papacy, the recognize-and-resist traditionalists are helping to ensure its continued and steady operation.

Image source: alamy.com

License: rights-managed

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation