Candid comments on the council…

“Cardinal” Avery Dulles in 1976: Vatican II reversed the Prior Magisterium, showed Value of Dissent

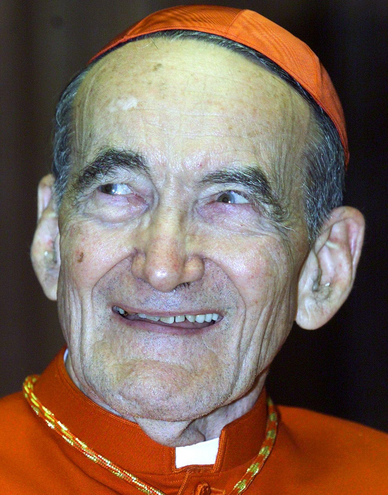

Fr. Avery Dulles, S.J., on Feb. 21, 2001

Fr. Avery Dulles, S.J., on Feb. 21, 2001

(image: REUTERS / Alamy Stock Photo)

Not that any more confirmation was needed, but it doesn’t hurt: Yes, Vatican II represents a genuine departure from the Roman Catholic magisterium.

Back in 1976, the Jesuit Fr. Avery Dulles (1918-2008) candidly acknowledged that the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) had contradicted and reversed the prior Catholic magisterium on sundry significant points of doctrine and discipline. This admission is noteworthy because most “orthodox” defenders of the council claim that a “correct interpretation” will show the continuity with prior teaching and debunk the allegations of rupture.

In addition to his frank assessment of the council’s obvious discontinuity with the prior magisterium, Dulles also contrasted the pre-conciliar Church’s treatment of the “New Theologians” — who, because they already held some of the very ideas that were later accepted by the council, were silenced and held in suspicion by the Holy Office under Pope Pius XII in the 1950s — with the Vatican II Church’s euphoric rehabilitation of those same characters.

Before we look at exactly what Dulles said, here is a little bit of background information.

Avery Dulles was a priest and theologian from the United States. He was ordained for the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) on June 16, 1956, and was made a “cardinal” by Antipope John Paul II in 2001 at the same fateful consistory at which a certain Jorge Bergoglio also received a red hat.

Fr. Avery is related to John Foster Dulles, U.S. Secretary of State from 1953-59, and Allen W. Dulles, director of the CIA from 1953-61.

As detailed on his Wikipedia page, Fr. Dulles had an impressive academic career. Until his death in 2008, he was considered an important theological voice in the Vatican II Church and was generally reputed to be part of the conservative camp.

From 1975-76, Dulles was president of the Catholic Theological Society of America. In that capacity, he gave an address at its 31st annual convention, in which he spoke on the role of the Catholic theologian and the magisterium. It is from this lecture that we will now present an excerpt.

Speaking in June of 1976, roughly 11 years after the close of Vatican II, Fr. Dulles did not mince words about how much the council differs from the pre-conciliar magisterium and how operative it was in legitimizing magisterial dissent:

Indirectly, … the Council worked powerfully to undermine the authoritarian theory [concerning the necessity of loyal submission to the magisterium] and to legitimate dissent in the Church. This it did in part by insisting on the necessary freedom of the act of faith and by attributing a primary role to personal conscience in the moral life. By contrast, the neo-Scholastic doctrine of the magisterium, with its heavy accentuation of intellectual obedience, minimizes the value of understanding and maturity in the life of faith [sic].

Most importantly for our purposes, Vatican II quietly reversed earlier positions of the Roman magisterium on a number of important issues. The obvious examples are well known. In biblical studies, for instance, the Constitution on Divine Revelation [Dei Verbum] accepted a critical approach to the New Testament, thus supporting the previous initiatives of Pius XII and delivering the Church, once and for all, from the incubus of the earlier decrees of the Biblical Commission. In the Decree on Ecumenism [Unitatis Redintegratio], the Council cordially greeted the ecumenical movement and involved the Catholic Church in the larger quest for Christian unity, thus putting an end to the hostility enshrined in Pius XI’s Mortalium animos. In Church-State relations, the Declaration on Religious Fredom [Dignitatis Humanae] accepted the religiously neutral State, thus reversing the previously approved view that the State should formally profess the truth of Catholicism. In the theology of secular realities, the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World [Gaudium et Spes] adopted an evolutionary view of history and a modified optimism regarding secular systems of thought, thus terminating more than a century of vehement denunciation of modern civilization.

As a result of these and other revisions of previously official positions, the Council rehabilitated many theologians who had suffered under severe restrictions with regard to their ability to teach and [be] published. The names of John Courtney Murray, Teilhard de Chardin, Henri de Lubac, and Yves Congar, all under a cloud of suspicion in the 1950’s, suddenly became surrounded with a bright halo of enthusiasm.

By its actual practice of revisionism, the Council implicitly taught the legitimacy and even the value of dissent. In effect the Council said that the ordinary magisterium of the Roman pontiff had fallen into error and had unjustly harmed the careers of loyal and able theologians. Thinkers who had resisted official teaching in the preconciliar period were the principal precursors of Vatican II.

(Rev. Avery Dulles, S.J., “Presidential Address: The Theologian and the Magisterium”, Proceedings of the Catholic Theological Society of America, vol. 31, pp. 240-241; underlining added.)

These words speak for themselves. Not only is Dulles rather direct about the changes in magisterial teaching, he is also clearly approving of them. Besides, his words seem to be dripping with contempt for the pre-conciliar (and only true) Catholic teaching authority. Dulles was definitely a man of Vatican II.

A few observations regarding this text are in order.

First, note that Dulles asserts that Vatican II’s reversal of the prior magisterium took place “quietly.” In other words, the council did not first acknowledge the prior teaching and then proceeded to modify or contradict it. Rather, it simply taught the new ideas and was hoping no one would notice — or at least not question it. That is why the council’s Decree on Ecumenism, for example, does not reference any of the pre-conciliar doctrinal pronouncements or disciplinary measures condemning and opposing ecumenical efforts at religious unity. It simply ignores them. Among the prior documents the council could have cited are the following:

- Pope Pius IX, Holy Office Letter to English Bishops on Christian Unity (1864)

- Pope Pius IX, Holy Office Instruction to Puseyite Anglicans on True Religious Unity (1865)

- Pope Pius IX, Apostolic Letter Iam Vos Omnes (1868)

- Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical Praeclara Gratulationis Publicae (1894)

- Pope Pius XI, Encyclical Mortalium Animos (1928)

- Pope Pius XII, Canonical Warning Cum Compertum on Attending Ecumenical Gatherings (1948)

- Pope Pius XII, Instruction De Motione Oecumenica on the Ecumenical Movement (1949)

Second, the fact that Dulles would use a word such as “incubus” to refer to the decrees of the Pontifical Biblical Commission, set up by Pope Leo XIII in 1902 to ensure the doctrinally sound intepretation of the Written Word of God, is a testimony to the contemptuous attitude of many Novus Ordo churchmen towards the sacred authority of the Apostolic See.

Third, by mentioning the rehabilitation of John Courtney Murray, Teilhard de Chardin, Henri de Lubac, and Yves Congar, Dulles is further confirming the rupture that Vatican II represents with respect to what was taught and believed before. When the very people who were held suspect of heresy, or had at least been forbidden from writing or teaching due to their dissent from right doctrine, suddenly become the star theologians for a (putative) ecumenical council just a few years later, that really drives home the point that a true rupture has taken place in matters of theology. (By the way: To see how much respect Fr. Congar had for the Holy Office which was censuring him, this story will give you an idea.)

Fourth, Dulles points out rather perspicaciously that by changing Catholic teaching, Vatican II basically legitimized (and rewarded) dissent from the magisterium. The message the council sent was as loud as it was clear: Dissent from Catholic teaching is good and valuable, and it may eventually pay off! Keep dissenting, because eventually the doctrine may change and you will be vindicated in your disbelief and disobedience!

However, here the Vatican II Modernists fall into the very pit they have dug for others (cf. Ps 7:16), because by encouraging dissent, the council did not only undermine the foundation of all magisterial authority, it also undermined itself. For if the Catholic teaching of centuries can be overturned, then all the more so can the teaching of a council of the 1960s. If dissent from the pre-Vatican II magisterium is legit, then so is dissent from the council itself and the post-conciliar magisteriun. Then each believer becomes his own magisterium, and that is essentially what we have witnessed in the past few decades: Most Novus Ordos do their own thing in matters of Faith and morals — with few exceptions, the idea of loyal submission to the Church does not exist in Novus Ordo Land.

By speaking so frankly about the superspreader of dissent that was Vatican II, Fr. Dulles has done the world a great favor. By no means, however, was he the only one to do so.

For example, Joseph M. White wrote in 1990 that Mgr. Joseph Clifford Fenton, a stalwart anti-Modernist theologian in the United States, battled “the Jesuit theologian John Courtney Murray over the latter’s unorthodox interpretation of church teaching on church-state relations” (The Diocesan Seminary in the United States: A History from the 1780s to the Present, p. 333; underlining added), stating further that “Murray’s dissenting position was adopted in the Declaration of Religious Freedom at Vatican Council II in 1964, and Fenton’s positions have been eclipsed” (ibid. See scan here). In other words, Vatican II adopted the unorthodox position, whereas the Catholic position, defended by Fenton, was abandoned. That tells us all we need to know.

The Jesuit Fr. Francis Sullivan (1922-2019) is another theologian who candidly acknowledged that

on several important issues the council clearly departed from previous papal teaching. One has only to compare the Decree on Ecumenism with such an encyclical as Mortalium animos of Pope Pius XI, or the Declaration on Religious Freedom with the teaching of Leo XIII and other popes on the obligation binding on the Catholic rulers of Catholic nations to suppress Protestant evangelism, to see with what freedom the Second Vatican Council reformed papal teaching.

(Francis A. Sullivan, S.J., Magisterium: Teaching Authority in the Catholic Church [Mahwah, NY: Paulist Press, 1983], p. 157)

“Mgr.” Thomas Guarino concedes this as well:

Surely the council represents a significant volte-face [about-face] on ecumenism. Mortalium animos casts doubt on the entire ecumenical enterprise, forbids Catholics from engaging in the movement, and comes close [sic] to calling Protestantism “a false Christianity, quite foreign to the one Church of Christ”… The Decree on Ecumenism [Unitatis Redintegratio of Vatican II], in contrast, warmly welcomes ecumenism, encouraging intelligent and active participation in it (UR §4). The discontinuity between the two documents is the source of consternation for some [sic] Catholics.

(Thomas G. Guarino, The Disputed Teachings of Vatican II: Continuity and Reversal in Catholic Doctrine [Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2018], pp. 108-109)

Guarino then proceeds to attempt to smooth over and justify this reversal, but that is beside the point here. The point is that there clearly is discontinuity, there is rupture, there is contradiction, between Vatican II and the preceding Magisterium, and even some “orthodox” Novus Ordo theologians are willing to say so.

All this goes to show that we are not dealing with doctrinal development but with doctrinal corruption.

More Resources on Vatican II:

- The Theological Errors of the Second Vatican Council: Resource Collection

- The Doctrinal Errors of the Second Vatican Council

- The Principal Heresies and Other Errors of Vatican II

- The Decrees of Vatican II Compared with Past Church Teachings

- The Vatican II Revolution: An Overview for Newcomers

- Can we read Vatican II “in Light of Tradition”?

- Book: Vatican II Exposed as Counterfeit Catholicism by Fathers Francisco and Dominic Radecki

- Did Vatican II Teach Infallibly?

- The Vatican II Diaries of Mgr. Joseph Clifford Fenton

- Vatican II behind the Scenes: Historical Testimony from 1963-64 confirms Theological “Bloodbath”

- Mgr. Fenton on the Failure of Vatican II

- The Catholic Theology of an Ecumenical Council vs. Vatican II

- The Council that could have been: The Original Vatican II Drafts

Image source: alamy.com (REUTERS/ Alamy Stock Photo; cropped)

License: rights-managed

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation