Old sermons published for first time in English…

“In Bread and Wine He Gives Himself Entirely”: Old Ratzinger Sermon denies Transubstantiation

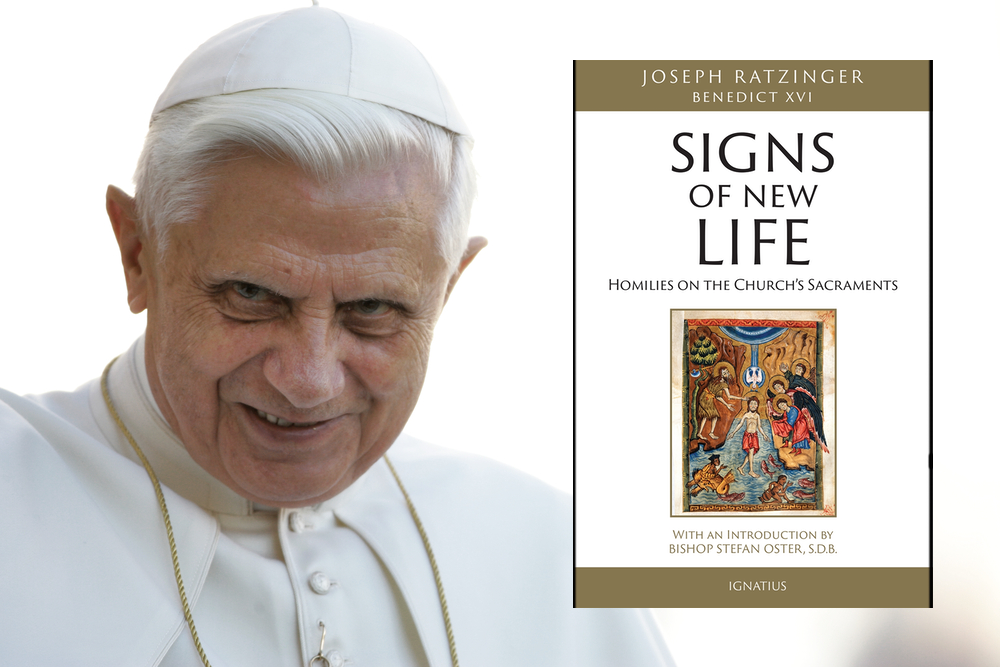

A few months ago, the Novus Ordo publisher Ignatius Press released a collection of sermons by the Modernist theologian Fr. Joseph Ratzinger, the man more commonly known today as “Pope Emeritus” Benedict XVI. The compendium is called Signs of New Life: Homilies on the Church’s Sacraments and was edited by “Fr.” Manuel Schlögl. It contains an introduction by “Bp.” Stefan Oster of Passau. The original German edition (Zeichen des neuen Lebens) was published in 2018.

In a glowing review of the book, “Fr.” Paul Scalia describes its contents as follows:

The book gathers homilies from throughout his episcopate, from his time as cardinal-archbishop of Munich and Freising through his pontificate as Benedict XVI. It provides two homilies on each of the seven sacraments. These 14 homilies are flanked at the beginning and the end by homilies on the Church, which herself is like a sacrament.

(Rev. Paul Scalia, “Benedict XVI on the Here-and-Now Reality of the Sacraments”, National Catholic Register, July 18, 2020)

For the purposes of this blog post, we will look at only one of these Ratzinger sermons, on the topic of the Holy Eucharist. Before we do so, however, it’s a good idea to familiarize people with the fact that the former “Cardinal” and “Pope” has the uncanny ability of putting out as catechetical material the most atrocious theological piffle. A single example shall suffice.

In a sermon preached for Lent 1981, the then-“Archbishop” of Munich and Freising taught a wholly novel concept of original sin, one that reeks of the existentialism of Martin Heidegger more than anything remotely Catholic. In any case, it is difficult to see how it wouldn’t escape the charge of heresy. See for yourself:

What does original sin mean, then, when we interpret it correctly?

Finding an answer to this requires nothing less than trying to understand the human person better. It must once again be stressed that no human being is closed in upon himself or herself and that no one can live of or for himself or herself alone. We receive our life not only at the moment of birth but every day from without – from others who are not ourselves but who nonetheless somehow pertain to us. Human beings have their selves not only in themselves but also outside of themselves: they live in those whom they love and in those who love them and to whom they are ‘present.’ Human beings are relational, and they possess their lives – themselves – only by way of relationship. I alone am not myself, but only in and with you am I myself. To be truly a human being means to be related in love, to be of and for. But sin means the damaging or the destruction of relationality. Sin is a rejection of relationality because it wants to make the human being a god. Sin is loss of relationship, disturbance of relationship, and therefore it is not restricted to the individual. When I destroy a relationship, then this event – sin – touches the other person involved in the relationship. Consequently sin is always an offense that touches others, that alters the world and damages it. To the extent that this is true, when the network of human relationships is damaged from the very beginning, then every human being enters into a world that is marked by relational damage. At the very moment that a person begins human existence, which is a good, he or she is confronted by a sin-damaged world. Each of us enters into a situation in which relationality has been hurt. Consequently each person is, from the very start, damaged in relationships and does not engage in them as he or she ought. Sin pursues the human being, and he or she capitulates to it.

(Joseph Ratzinger, ‘In the Beginning…’: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall, trans. Boniface Ramsey, O.P. [Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1995], pp. 72-73.)

(We must point out here, as a matter of justice, that the awful inclusive language in this quote is that of the translator — it is not in Ratzinger’s original.)

Notice that the concept of sanctifying grace is entirely absent, as is any mention of soul. For the Modernist Ratzinger, original sin is a matter of damaged or disturbed human relationships, which every human being is necessarily confronted with — an entirely Naturalistic idea. The true Catholic understanding of original sin, on the other hand, is that it consists of the loss of sanctifying grace in the soul transmitted through natural generation to the children of Adam — a supernatural matter.

Pope Pius XI gave a very succinct refresher on original sin in his encyclical against the errors of the German National Socialists:

“Original sin” is the hereditary but impersonal fault of Adam’s descendants, who have sinned in him (Rom. v. 12). It is the loss of grace, and therefore of eternal life, together with a propensity to evil, which everybody must, with the assistance of grace, penance, resistance and moral effort, repress and conquer. The passion and death of the Son of God has redeemed the world from the hereditary curse of sin and death.

(Pope Pius XI, Encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge, n. 25)

Apparently Fr. Ratzinger never got the memo. Or rather, he did get the memo and consigned it to the garbage can. No wonder, then, that in 1956 his second doctoral dissertation got rejected for Modernism, thanks to the watchful eye of Fr. Michael Schmaus, who recognized Ratzinger’s dangerous theology early on.

With this in the back of our minds, we are now properly prepared to look at one of the Ratzinger sermons on the Holy Eucharist contained in Signs of New Life. It is ominously entitled “In Bread and Wine He Gives Himself Entirely.”

For copyright reasons, we cannot simply reproduce the sermon here in its entirety. However, it is possible to read the entire text online for free by means of this Google Books preview:

As the preview edition does not show any page numbers, we cannot refer to a particular page, but the sermon can be found by navigating the table of contents. Also, we can reference the Kindle location for those who have the electronic version sold by Amazon (not that we encourage anyone to obtain this theological poison). The sermon begins at loc. 742.

What is wrong with Ratzinger’s discourse on the Eucharist? In a nutshell: It is filled with references to (natural) bread, makes no reference to the dogma of Transubstantiation (neither the term nor the concept), and everything he says is easily compatible with heretical notions of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, such as Luther’s Consubstantiation or Schillebeeckx’s Transignification.

Here are a few direct quotations taken from the Ratzinger homily:

- “Jesus, as a sign of his presence, chose bread and wine. With each one of these two signs he gives himself completely, not only in part…. He is a person who, through signs, comes near to us and unites himself to us.”

- “The prayer with which the Church, during the liturgy of the Mass, consigns this bread to the Lord, qualifies it as fruit of the earth and the work of humans.”

- “In this way, we begin to understand why the Lord chooses this piece of bread to represent him.”

- “…in some way, we detect in the piece of bread, creation is projected toward divinization, toward the holy wedding feast, toward unification with the Creator himself. And still, we have not yet explained in depth the message of this sign of bread.”

- “Through his gratuitous suffering and death, he became bread for all of us and, with this, living and certain hope.”

- “In a very similar way, the sign of wine speaks to us.”

- “On the feast of Corpus Christi, we especially look at the sign of bread.”

- [addressing God:] “Give men and women bread for body and soul!”

To understand these words in their context, the interested reader can peruse the entire homily at the link to Google Books given above. There he will read a lot about signs, bread, flour, grinding and baking, but nothing about the real and substantial Presence of Jesus Christ. Yet, the Catholic dogma is clear:

If anyone denies that in the sacrament of the most holy Eucharist there are truly, really, and substantially contained the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and therefore the whole Christ, but shall say that He is in it as by a sign or figure, or force, let him be anathema.

(Council of Trent, Session 6, Canon 1; Denz. 883)

The fact that Fr. Ratzinger also speaks of a “consecrated Host” “through which [Christ] gives himself” is not proof that he is teaching Transubstantiation. Lutherans, Anglicans, and certain other Protestants also believe in the consecration of the host and the chalice at their “Lord’s Supper”, and that Christ is somehow received in and through the Eucharist, but they reject the dogma of Transubstantiation.

Likwise, Ratzinger’s comment in the same sermon that Christ “wants to transform us as he transformed the Host” is no evidence for belief in Transubstantiation. On the contrary, since man obviously cannot be transubstantiated (i.e., undergo a change in his substance while his accidents remain), it is yet another indicator that Ratzinger rejects this beautiful dogma of the Catholic Faith.

Now, to be clear: Ratzinger has affirmed belief in Transubstantiation in other places. In fact, in the other sermon on the Eucharist in the same book, entitled “Transformation Occurs in Prayer”, he speaks of “the bread that is consecrated, transformed, transubstantiated” (loc. 700).

Also, back in 1967, Ratzinger published an essay entitled “The Problem of Transubstantiation and the Question about the Meaning of the Eucharist” (Das Problem der Transubstantiation und die Frage nach dem Sinn der Eucharistie) in the journal Theologische Quartalschrift (vol. 147, pp. 129-158). It was translated into English and published as part of his Collected Works (vol. 2, Theology of the Liturgy [Ignatius Press, 2014], pp. 218-242).

And in his book God Is Near Us (Ignatius Press, 2003), he speaks of “the mystery of transubstantiated bread” (loc. 855) and notes that “the Church calls [the change that occurs in the Eucharist] transubstantiation” (loc. 1013) and that she “insists on ‘change of substance'” (loc. 1024).

Precisely what he understands by that dogma, however, is anyone’s guess:

Whenever the Body of Christ, that is, the risen and bodily Christ, comes, he is greater than the bread, other, not of the same order. The transformation happens, which affects the gifts we bring by taking them up into a higher order and changes them, even if we cannot measure what happens. When material things are taken into our body as nourishment, or for that matter whenever any material becomes part of a living organism, it remains the same, and yet as part of a new whole it is itself changed. Something similar happens here. The Lord takes possession of the bread and the wine; he lifts them up, as it were, out of the setting of their normal existence into a new order; even if, from a purely physical point of view, they remain the same, they have become profoundly different.

(Joseph Ratzinger, God Is Near Us: The Eucharist, the Heart of Life [San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2003], p. 86)

Ratzinger’s words are particularly disturbing when we recall that Pope Clement XIII warned “that diabolical error, when it has artfully colored its lies, easily clothes itself in the likeness of truth while very brief additions or changes corrupt the meaning of expressions; and confession, which usually works salvation, sometimes, with a slight change, inches toward death” (Encyclical In Dominico Agro, n. 2).

The dogma of Transubstantiation is not terribly complicated and can be explained quite straightforwardly. No, the Lord does not “take possession” of the bread and wine, nor does He “lift them up” into some “new order”. Rather, by His almighty power, He converts the substance of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ, such that bread and wine cease to exist entirely, their accidents (appearances) alone remaining. By “substance” here we do not mean what modern empirical science understands by the term (which is perceptible by the senses), but rather the scholastic-philosophical notion of substance as that which makes a thing to be what it is, that in which its accidents inhere, that which the accidents are accidents of (which is not perceptible by the senses but is known by the intellect).

What, then, do we make of Ratzinger’s position? Does he have a clear and consistent position? If he doesn’t believe in Transubstantiation, why does he purport to be teaching it in some places? And if he does believe in Transubstantiation, why does he undermine it with ambiguity and apparent denials in other places?

Ladies and gentlemen, these two questions can be answered very easily by calling to mind that in Joseph Ratzinger we are dealing with a Modernist. In 1794, Pope Pius VI condemned the proto-Modernists of the synod of Pistoia (a local council held in the Italian city in 1786). They, much like today’s innovators, promoted error using ambiguous language under the pretext of meaning to “reform” the Church. At times they were even content to contradict themselves so as to be able to claim that they had been but misunderstood and were in fact orthodox.

Pope Pius roundly condemned such shenanigans in the preamble to his celebrated bull Auctorem Fidei:

They [prior Popes and bishops] knew the capacity of innovators in the art of deception. In order not to shock the ears of Catholics, the innovators sought to hide the subtleties of their tortuous maneuvers by the use of seemingly innocuous words such as would allow them to insinuate error into souls in the most gentle manner. Once the truth had been compromised, they could, by means of slight changes or additions in phraseology, distort the confession of the faith that is necessary for our salvation, and lead the faithful by subtle errors to their eternal damnation. This manner of dissimulating and lying is vicious, regardless of the circumstances under which it is used. For very good reasons it can never be tolerated in a synod of which the principal glory consists above all in teaching the truth with clarity and excluding all danger of error.

Moreover, if all this is sinful, it cannot be excused in the way that one sees it being done, under the erroneous pretext that the seemingly shocking affirmations in one place are further developed along orthodox lines in other places, and even in yet other places corrected; as if allowing for the possibility of either affirming or denying the statement, or of leaving it up the personal inclinations of the individual – such has always been the fraudulent and daring method used by innovators to establish error. It allows for both the possibility of promoting error and of excusing it.

It is as if the innovators pretended that they always intended to present the alternative passages, especially to those of simple faith who eventually come to know only some part of the conclusions of such discussions, which are published in the common language for everyone’s use. Or again, as if the same faithful had the ability on examining such documents to judge such matters for themselves without getting confused and avoiding all risk of error. It is a most reprehensible technique for the insinuation of doctrinal errors and one condemned long ago by our predecessor St. Celestine who found it used in the writings of Nestorius, bishop of Constantinople, and which he exposed in order to condemn it with the greatest possible severity. Once these texts were examined carefully, the impostor was exposed and confounded, for he expressed himself in a plethora of words, mixing true things with others that were obscure; mixing at times one with the other in such a way that he was also able to confess those things which were denied while at the same time possessing a basis for denying those very sentences which he confessed.

In order to expose such snares, something which becomes necessary with a certain frequency in every century, no other method is required than the following: Whenever it becomes necessary to expose statements that disguise some suspected error or danger under the veil of ambiguity, one must denounce the perverse meaning under which the error opposed to Catholic truth is camouflaged.

(Pope Pius VI, Apostolic Constitution Auctorem Fidei, preamble; underlining added.)

When perusing Ratzinger’s sermon “In Bread and Wine He Gives Himself Entirely,” it is not difficult to see that the principal focus of the entire discourse is bread. What is more, it is even blasphemously hinted that bread and wine are offered to God at Holy Mass and not the literal Body and Blood of Christ!

The whole notion of offering the “work of human hands” takes its origin, as Fr. Anthony Cekada shows in his book Work of Human Hands (pp. 287-288), in the thought of the heretical Jesuit Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955). The following video explains this as well:

So, to sum up: In his sermon, Ratzinger does not teach the dogma of Transubstantiation. Nowhere does he unequivocally affirm it. In fact, if one takes his words in their natural sense, one will conclude that he is denying it. If an objective reader did not know that the author of these words claimed to be a Roman Catholic, he would probably infer that they were written by a Lutheran or an Anglican. The only way to reconcile Ratzinger’s words with the dogma of Transubstantiation would be to deliberately and artificially put a spin on them so as to “force” them into an orthodox sense.

Now, inevitably someone will object that since the homilies in Signs of New Life are all from Ratzinger’s pre-Benedict period, with most of them probably preached in the late 1970s (he occupied the diocese of Munich-Freising from 1977 until 1982), we should assume that Ratzinger “has changed”, that he no longer holds any heretical views expressed therein.

This, however, is definitively ruled out by what the book’s editor writes in his foreword, namely, that Benedict XVI “reviewed once again the previously unpublished texts and with his characteristic generosity agreed to their publication…” (loc. 42). In other words, Ratzinger just placed his stamp of approval on them once more, so that dog won’t hunt.

Also, some may be tempted to argue that perhaps Ratzinger considers Transubstantiation to be one of several legitimate ways of “interpreting” the Holy Eucharist. But even that idea is condemned by the Catholic Church. There is only one truth about the Eucharistic Presence, and it is that which has been defined dogmatically by the Church at the Council of Trent under the most appropriate label “Transubstantiation.”

Again we turn to Pope Pius VI’s denunciation of the robber synod of Pistoia (its parallels to Vatican II are enormous, by the way). One of the many errors condemned by the Pope was its doctrine on the Holy Eucharist, even though it correctly affirmed the content of the dogma of Transubstantiation. What, then, was the Pius VI’s reason for rejecting it? It did not use the word “Transubstantiation”. See for yourself:

The doctrine of the synod, in that part in which, undertaking to explain the doctrine of faith in the rite of consecration, and disregarding the scholastic questions about the manner in which Christ is in the Eucharist, from which questions it exhorts priests performing the duty of teaching to refrain, it states the doctrine in these two propositions only: 1) after the consecration Christ is truly, really, substantially under the species; 2) then the whole substance of the bread and wine ceases, appearances only remaining; it (the doctrine) absolutely omits to make any mention of transubstantiation, or conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the body, and of the whole substance of the wine into the blood, which the Council of Trent defined as an article of faith, and which is contained in the solemn profession of faith; since by an indiscreet and suspicious omission of this sort knowledge is taken away both of an article pertaining to faith, and also of the word consecrated by the Church to protect the profession of it, as if it were a discussion of a merely scholastic question,–dangerous, derogatory to the exposition of Catholic truth about the dogma of transubstantiation, favorable to heretics.

(Pope Pius VI, Apostolic Constitution Auctorem Fidei, error no. 29; Denz. 1529; underlining added.)

The significance of this papal judgment cannot be overstated. Pius VI condemned failure to use the term “Transubstantiation” in the explanation of the Real Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, and he also denounced attempts to dismiss the issue as merely an academic (scholastic) matter.

Denying Transubstantiation is quite the fad in Novus Ordo Land, not just among the clueless pewsitters — most of whom truly don’t know better because they were never taught — but also among academics and high-ranking clergy. For example, “Cardinal” Gerhard Ludwig Müller, whom Ratzinger (as Benedict XVI) appointed head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 2012, is another Transubstantiation denier. The doctrine he teaches may be called “Transcommunication”; and he goes so far as to affirm that the question at what precise moment Christ becomes present in the Holy Eucharist does not even make sense. We have exposed and refuted his pseudo-intellectual bunk in the following post:

It makes sense, then, that Müller was chosen to be the editor-in-chief of the German original editions of Ratzinger’s Collected Works. He doesn’t believe in Catholicism either.

Since Catholic belief underlies Catholic practice, false theology will always, before long, result in a corruption of Catholic practice. The “New Mass” of Paul VI and his entire liturgical revolution is the most visible fruit of the changes in theology introduced by the Second Vatican Council.

We must not be surprised, then, by how Fr. Ratzinger spoke about the beautiful and pious Catholic practice of making a visit to the Blessed Sacrament, in a lecture given in 1965:

Eucharistic adoration or a quiet visit in church, if it is to make sense, cannot simply be a conversation with the God who is thought to be present in a circumscribed locality. Statements such as “God dwells here” and conversations with the “local” God that are justified in this way manifest a misunderstanding of both the Christian mystery and the concept of God that is necessarily repellent to a thinking man who knows about God’s omnipresence. If someone wished to justify going to church on the grounds that one must pay a visit to the God who is present only there, then that would in fact be a reason that made no sense and would rightly be rejected by modern man. Eucharistic adoration is in truth related to the Lord, who through his historical life and suffering has become “Bread” for us; in other words, through his Incarnation and self-abandonment to death he has become the One who is open for us. Such prayer is therefore related to the historical mystery of Jesus Christ, to God’s history with men that moves toward us in the sacrament. And it is related to the mystery of the Church: since it is related to the history of God with men, it is related to the whole “Body of Christ”, to the community of believers, in which and through which God comes to us. In this way praying in church and before the Blessed Sacrament is the “classification” of our relation to God under the mystery of the Church as the specific locality where God meets us. And finally, this is the purpose of our going to church at all: so that I in an orderly fashion may take my place in God’s history with men-the only setting in which I as a man have my true human existence and which alone therefore also opens up for me the true space of my encounter with God’s eternal love.

(Joseph Ratzinger, Die sakramentale Begründung christlicher Existenz [Meitingen and Freising: Kyrios, 1966], pp. 26-27; translated by Kenneth Baker and Michael J. Miller as “The Sacramental Foundation of Christian Existence”, in Theology of the Liturgy [San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2014], pp. 167-168; loc. 3290; underlining added.)

Got it?! So much for Fr. Francis X. Lasance’s Prisoner of Love dwelling in the tabernacle.

Ratzinger’s theology is what Pope St. Pius X was talking about, in essence, when he wrote that “all terms smacking of an unhealthy novelty in Catholic publications are condemnable, such as those deriding the piety of the faithful, or pointing out a new orientation of the Christian life, new directions of the Church, new aspirations of the modern soul, a new social vocation of the clergy, or a new Christian civilization” (Encyclical Pieni L’Animo, n. 12).

Keep in mind that an immense amount of the official (and magisterial) “Catholic” theology since Vatican II has been shaped by the mind of Joseph Ratzinger, who was not only a mover and shaker at the council itself and, of course, “Pope” from 2005 until 2013, but was also the head of the Vatican’s doctrinal office well over 20 years, from 1982 until 2005.

Our Blessed Lord had instructed us on how to spot the enemy within:

Even so every good tree bringeth forth good fruit, and the evil tree bringeth forth evil fruit. A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, neither can an evil tree bring forth good fruit. Every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit, shall be cut down, and shall be cast into the fire. Wherefore by their fruits you shall know them.

(Matthew 7:17-20)

What are the fruits of the theology of Joseph Ratzinger?

Image source: own composite with elements from shutterstock.com and amazon.com

License: paid and fair use

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation