A Response to Critics…

“Heretical Popes” & Vatican I:

A Follow-Up

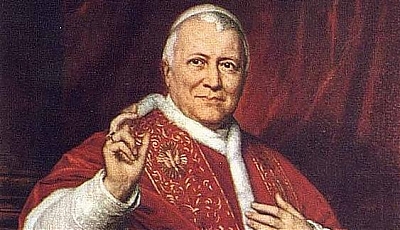

The First Vatican Council was called by the longest-reigning Pope in history: Pius IX (1846-1878)

Our post of April 7 discussing the question of “heretical” Popes in light of testimony given by Archbishop John Purcell (1800-1883) that the Fathers of the First Vatican Council said such a thing was impossible, has generated plenty of interest and discussion among sedevacantists and non-sedevacantists.

It was to be expected that this latest piece of evidence for Sedevacantism wasn’t going to sit well with our critics, and so it comes as no surprise that some have tried to accuse us of “taking things out of context” and of “cherry-picking quotes”. Specifically, the argument has been advanced that the larger context of Abp. Purcell’s intervention supposedly shows that the question being answered was not that of a Pope who is a heretic, but a Pope who attempts to define heresy ex cathedra (i.e. by making an infallible dogmatic pronouncement).

But is this really what the larger context shows? Thankfully, the book which contains Abp. Purcell’s report is available online for free, from the following sources, so everyone can verify the context for himself (the chapter that contains the text under discussion is found on pp. 227-243):

- Google Books – The Life and Life Work of Pope Leo XIII

- Internet Archive – The Life and Life Work of Pope Leo XIII

Before we get into the details regarding the context, let us look again at the excerpt we provided in our original post, which speaks for itself. This time, we are rendering certain key phrases in red bold print to make sure our critics don’t miss what the text clearly says:

The question was also raised by a Cardinal, “What is to be done with the Pope if he becomes a heretic?” It was answered that there has never been such a case; the Council of Bishops could depose him for heresy, for from the moment he becomes a heretic he is not the head or even a member of the Church. The Church would not be, for a moment, obliged to listen to him when he begins to teach a doctrine the Church knows to be a false doctrine, and he would cease to be Pope, being deposed by God Himself.

If the Pope, for instance, were to say that the belief in God is false, you would not be obliged to believe him, or if he were to deny the rest of the creed, “I believe in Christ,” etc. The supposition is injurious to the Holy Father in the very idea, but serves to show you the fullness with which the subject has been considered and the ample thought given to every possibility. If he denies any dogma of the Church held by every true believer, he is no more Pope than either you or I; and so in this respect the dogma of infallibility amounts to nothing as an article of temporal government or cover for heresy.

(Abp. John B. Purcell, quoted in Rev. James J. McGovern, Life and Life Work of Pope Leo XIII [Chicago, IL: Allied Printing, 1903], p. 241)

This isn’t difficult to understand. As the words in red bold print clearly reveal, the question that was asked, considered, and responded to was what would happen if the Pope were to depart from the Faith himself, if he were to become a heretic — not if he were to attempt to define as dogma something that is heretical. The two questions are somewhat related, of course, but it is nonsense and calumnious to accuse us of somehow “twisting” the text — the text is as plain as it could be. What would happen if the Pope should start professing heresy? He would cease to be Pope, that’s what, just as any other Catholic who begins to profess heresy would cease being a member of the Church! And as we likewise explained in our last post on this — and this is something our critics have so far ignored — the reason for this is that the Church cannot be divided in her Faith; she has but one Faith, as she has but one Lord and one baptism (see Eph 4:4). It is impossible to profess a different religion and still be a member — much less head — of the Catholic Church: “Actually only those are to be included as members of the Church who have been baptized and profess the true faith…” (Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Mystici Corporis, n. 22).

All of this couldn’t be more clear. Besides, in the quote by Abp. Purcell, as reproduced above, the keywords are not “define” or “declare”, but rather, “becomes [a heretic]”, “say”, and “deny”. We are clearly talking about a Pope becoming a heretic, a Pope who professes or fails to profess a particular teaching; we are not talking about a Pope who attempts to define heresy infallibly. True, the text also says that the Church “would not be … obliged to listen to him when he begins to teach” a heresy, but of course this is true as well, because he is then no longer Pope, as the rest of the quote painstakingly points out. Obviously the hypothetical scenario of a Pope who is a heretic brings with it the scenario of such a Pope teaching his heresy. That’s why the text speaks about a Pope both being a heretic and teaching heresy — and in that very order.

This should really settle the issue, but some people prefer illusion to reality if the reality is sufficiently inconvenient.

First appointed by Pope Gregory XVI, Abp. John Baptist Purcell

headed the (arch)diocese of Cincinnati for over 50 years

So what about the larger context? It has been argued that what Abp. Purcell said before this passage “proves” that the text we quoted refers not to a Pope being a heretic but to a Pope trying to define heresy infallibly. Really? Let’s see. Here is what Abp. Purcell says immediately prior to what we quoted in our original post (for even more context, everyone can download a copy of the book in electronic format, as linked above, and read the entire chapter):

Then I said, you tell us that there were some forty Popes in the early ages, who taught what is now regarded as an erroneous doctrine by some. Cardinal Bellomang [sic — he must have meant Bellarmine] gives us the names of them and tells us what was taught. He tells us what was the nature of their teachings to a great extent. Now, says I, there are a great cloud of witnesses over our heads — these forty Popes. I called them one by one, and I said, Honorius, why do you teach that there is but one will of Christ, when there is a divine will of Christ as God, and a human will of Christ as man. Now, why should you say there is but one will? This definition has caused a great deal of trouble. It created schisms and differences of opinions, etc., in the Church. He never should have done so. This was his fault. He should have instructed that the two wills of Christ were not incompatible.

Then I said to the council, in passing over this subject, here is another of these papers over our heads, as I imagine it was over Nicholas I. He taught that the baptism in the name of Jesus was all-sufficient, without the name of the Father and Holy Ghost. That he should not have taught. He was mistaken in that, and the Church says so now, and that he never should have taught the like. Here is John XXII., who teaches from the pulpit, and wishes others to teach, that those who died in the peace of God with the peace of God on their lips are [sic — the word “not” seems to be missing] in beatific condition until the day of judgment. Here, again, three great Bishops of the sixth, seventh, and eighth general councils called Honorius heretical. Were we to consider those teachings ex cathedra on those occasions, and pronounce an anathema? I will not delay you by adverting to other instances of the kind, but I was most happy to hear the entire council, as one man, concerning those of whom I spake, answer me, “Those Popes never addressed such doctrines to the universal Church. They only spoke to individuals. They did not speak as pastors of His universal Church, therefore they did not speak ex cathedra.” I cannot tell you what a load that removed from my mind, when I heard that expression that those teachings were not ex cathedra, and therefore not binding on our action, and that our action would not be retroactive as binding on the teachings of those Bishops.

I told the Cardinals in the council that there was another and a weightier objection which I wished to have removed before I gave my assent to that dogma, and that was, how we are to understand the claims of Boniface VIII., who said, “Two swords are given me by God — the spiritual and the temporal!” I sought in the Dominican library of the Minerva in Rome to refresh my memory, and to see on what grounds they claim the right of controlling temporary affairs; of deposing Henry VIII. or Elizabeth, or any other temporal prince, and absolving their vassals from their oath of allegiance, if their sovereigns did not respect the act of excommunication by the Church. I could not find any text of authority for that in the Bible. Hence I wanted the council to say whether they asserted a right of that kind or assumed it as a right, and the entire council with one voice cried out: “Those Popes had no authority, no commission from God to pretend to any such power.” Well, I told them, Thank God, I have spoken and had it decided by this council, instead of assuming the resposibility of those by-gone times. The day has gone by when such things were possible, and were believed of force, and we have done a great deal by having these two important matters settled.

The question was also raised by a Cardinal, “What is to be done with the Pope if he becomes a heretic?”… [here the quote in our original post begins]

(Abp. John B. Purcell, quoted in Rev. James J. McGovern, Life and Life Work of Pope Leo XIII [Chicago, IL: Allied Printing, 1903], pp. 239-241; paragraph breaks added to facilitate reading.)

Abp. Purcell says a lot here, and a lot that needs to be qualified, but that is beside the point now. The question under discussion in this post is whether these paragraphs just quoted in any way change the meaning of what the archbishop said about what is to be done if the Pope were to become a heretic. But if anything, this text is further evidence that the Pope-heretic scenario speaks of a Pope being a heretic and not as him defining heresy, because Abp. Purcell basically already touched upon the latter scenario in his comments about Pope Honorius: “Here, again, three great Bishops of the sixth, seventh, and eighth general councils called Honorius heretical. Were we to consider those teachings ex cathedra on those occasions, and pronounce an anathema?”

There it is — the scenario of a heresy being defined by a Pope, in light of papal infallibility. Purcell treated Honorius’ letter to Sergius as an ex cathedra definition and tested the response of the assembled Council Fathers: “This definition has caused a great deal of trouble.” And how did they respond? “Those Popes never addressed such doctrines to the universal Church. They only spoke to individuals. They did not speak as pastors of His universal Church, therefore they did not speak ex cathedra.”

So, the entire matter our critics are trying to squeeze into Purcell’s Pope-heretic passage from our original post, was already addressed and resolved in the pages leading up to that passage. It therefore would have made no sense for the archbishop to bring the issue up again in another passage. Instead, a similar but essentially different question was brought up: What if the Pope were to, not define a heresy, but simply become a heretic, that is, depart from the Faith? Could he, for example, still issue infallible declarations, under the criteria being considered by the Council Fathers? Would they have to listen to a heretic, in other words? This is where the answer was given as follows: “It was answered that there has never been such a case; the Council of Bishops could depose him for heresy, for from the moment he becomes a heretic he is not the head or even a member of the Church. The Church would not be, for a moment, obliged to listen to him when he begins to teach a doctrine the Church knows to be a false doctrine, and he would cease to be Pope, being deposed by God Himself.”

So where is the problem? Two different issues were brought up and answered separately. There really is no difficulty at all, except that our critics are desperate to create one because they don’t like that the Council Fathers essentially sanctioned one of the main principles of Sedevacantism: a heretic cannot be Pope because he is not a member of the Church. Sorry, but the “context” argument just isn’t going to work as a refutation.

Of course, it is true that the larger frame of reference for the council was the exercise of the papal magisterium, the Pope’s teaching office, because with regard to the papacy that is what the council primarily concerned itself with. But this context doesn’t somehow neutralize or relativize what was said about what would happen if a Pope were to become a heretic. The inquiring cardinal was concerned about whether he would have to submit to a heretic claiming the papal office, specifically as concerns his teaching authority if the council defines that a Pope can issue dogmatic definitions that are infallible and irreformable. How was this going to work if the Pope himself professes heresy? Would the Church then have to consider as infallible the dogmatic pronouncements of a heretic? Would this not open the floodgates to the possibility of a heresy being defined as dogma? This is the context, and the answer speaks for itself.

On the other hand, if our critics were right in what they maintain about the statements of Abp. Purcell referring to a dogmatic definition of heresy, and not to a Pope being a heretic, then this is how his report would have read:

[How Abp. Purcell’s text would read if our critics were right:]

The question was also raised by a Cardinal, “What is to be done with the Pope if he dogmatically defines a heresy?” It was answered that there has never been such a case; the Council of Bishops could depose him for heresy, for from the moment he defines heresy he is not the head or even a member of the Church. The Church would not be, for a moment, obliged to listen to him when he begins to teach a doctrine the Church knows to be a false doctrine, and he would cease to be Pope, being deposed by God Himself.

If the Pope, for instance, were to define that the belief in God is false, you would not be obliged to believe him, or if he were to define that the rest of the creed is false, “I believe in Christ,” etc. The supposition is injurious to the Holy Father in the very idea, but serves to show you the fullness with which the subject has been considered and the ample thought given to every possibility. If he defines any heresy denied by every true believer, he is no more Pope than either you or I; and so in this respect the dogma of infallibility amounts to nothing as an article of temporal government or cover for heresy.

Note how different this is from what the text actually says.

Consider also that the dogma of papal infallibility makes the very notion of a heretical ex cathedra statement impossible. The whole point of the Vatican Council’s dogma of papal infallibility is that a Pope cannot err in his dogmatic definitions; he would drop dead before he could promulgate a heretical dogma — that’s the protection of the Holy Ghost. But as our critics would apparently have it, papal infallibility supposedly means that that a true reigning Pope is able to make a heretical ex cathedra pronouncement — but then in the act ceases to be Pope. Is this not a novelty? Where has the Church ever taught such a thing?

In fact, such an idea would seriously weaken the dogma, because in practice it would then be reduced to meaning that a Pope can define anything he likes; it’s just incumbent upon the cardinals then to spring into action and declare him a heretic and remove him. In that case, the dogma of infallibility would really not protect the Pope at all, because the a priori protection that divinely prevents an error in a dogmatic definition would thus mean nothing more than an a posteriori (after-the-fact) validation by cardinals to ensure that the definition is not heretical. Thus the entire protective purpose of the dogma would be turned on its head, as though infallibility simply meant that if the Pope defines something dogmatically that is heretical, lower-ranking Church authorities will see to it that he gets declared a heretic and removed. All the doctrinal power would then lie with the cardinals, it seems, and not with the Pope.

Another consideration, often glossed over, is that not only does an ex cathedra definition preclude heresy from being defined, but any error whatsoever. It isn’t just a protection against heresy but against anything that is false regarding faith or morals. So if our critics were right, it would not make any sense to ask what would happen if the Pope were to define a heresy; instead, it would need to be asked what would happen if the Pope were to define something that is erroneous, even if the error is not heretical but of some lesser degree of doctrinal falsity.

Before we conclude, a quick note on the objections Abp. Purcell raised regarding some Popes of the past who allegedly taught error: It is beyond the scope of this post to address these in detail, because the objective here is merely to defend our original post against those who claim that we had misrepresented the words of Abp. Purcell and that the Council Fathers really did not address the issue of a Pope who becomes a heretic but of a Pope who definesheresy.

Our ongoing series of blog posts called The “Heretical” Popes examines and refutes the different arguments brought against the “suspect” Popes of the past; it is there that we delve into various accusations in detail. So far, we have published one installment, on Pope Adrian VI. Our next one will be on Pope Honorius I, and we will show that not only did he not profess heresy, he also was not in fact condemned as a heretic. As far as Pope Nicholas goes, a brief summary of the controversy with some insightful finds can be found in “The ‘Error’ of Pope Nicholas I”. Finally, let us not forget that Abp. Purcell himself qualified that the earlier Popes he was criticizing “taught what is now regarded as an erroneous doctrine by some”, thus conceding that there was no consensus among theologians that the examples he was giving of alleged papal error were in fact papal error for sure. In any case, as the council only concerned itself in its dogmatic definition with infallible ex cathedra statements, and since this is what Abp. Purcell was specifically asking about, the Fathers were happy to point out that none of the cases cited, even if genuine, met all the criteria for an infallible pronouncement; therefore, Purcell’s concerns were unfounded.

Thus far our inquiry into the words of Abp. Purcell about the First Vatican Council, and the responses given by the assembled bishops. Clearly, all the available evidence confirms that our original post was quite correct in presenting what was said as a rejection of the possibility of a heretical Pope. The full context of Abp. Purcell’s report underscores this contention, namely, that were a true Pope to depart from the Faith by becoming a heretic, he would immediately cease to be Pope and could be judged and removed by the Church, having been deposed by God Himself.

Dear critics, please just deal with it.

Image sources: Wikimedia Commons / Wikimedia Commons

Licenses: public domain / public domain

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation