Apostolic Letter of Pope Leo XIII

to the Archbishop of Paris

Epistola Tua (1885)

Apostolic Letter of His Holiness Pope Leo XIII on the submission that is incumbent on writers as regards religious affairs and the action of the Church in relation to Catholic society

LEO, BISHOP,

SERVANT OF THE SERVANTS OF GOD,

IN PERMANENT MEMORY OF THE MATTER

Your filial letter addressed to Us, a letter filled with the most refined feelings of love and sincere devotion, has soothed with sweet comfort Our spirits, which have been afflicted by a recent and heavy sadness. You well know that nothing can more grievously concern us than seeing the spirit of harmony among Catholics disturbed, the peace of souls shaken, trust emptied, and the submission befitting children to the fatherly authority that governs them discarded. Consequently, at the very first sign of this disaster, we cannot help being sorely vexed and having a care to prevent danger straightaway.

Therefore, the recent publication of a certain written work, from a source that had been less expected and which you also deplore, the stir that arose out of it, and the comments that it caused, enjoin me to remain by no means silent on a matter, the consideration of which, even if perhaps it may turn out to be unpleasant, will still for this reason not be less useful both in France and even elsewhere.

By certain indications it is not difficult to conclude that among Catholics – doubtless as a result of current evils – there are some who, far from satisfied with the condition of “subject” which is theirs in the Church, think themselves able to take some part in her government, or at least, think they are allowed to examine and judge after their own fashion the acts of authority. A misplaced opinion, certainly. If it were to prevail, it would do very grave harm to the Church of God, in which, by the manifest will of her Divine Founder, there are to be distinguished in the most absolute fashion two parties: the teaching and the taught, the Shepherd and the flock, among whom there is one who is the head and the Supreme Shepherd of all.

To the shepherds alone was given all power to teach, to judge, to direct; on the faithful was imposed the duty of following their teaching, of submitting with docility to their judgment, and of allowing themselves to be governed, corrected, and guided by them in the way of salvation. Thus, it is an absolute necessity for the simple faithful to submit in mind and heart to their own pastors, and for the latter to submit with them to the Head and Supreme Pastor. In this subordination and dependence lie the order and life of the Church; in it is to be found the indispensable condition of well-being and good government. On the contrary, if it should happen that those who have no right to do so should attribute authority to themselves, if they presume to become judges and teachers, if inferiors in the government of the universal Church attempt or try to exert an influence different from that of the supreme authority, there follows a reversal of the true order, many minds are thrown into confusion, and souls leave the right path.

And to fail in this most holy duty it is not necessary to perform an action in open opposition whether to the Bishops or to the Head of the Church; it is enough for this opposition to be operating indirectly, all the more dangerous because it is the more hidden. Thus, a soul fails in this sacred duty when, at the same time that a jealous zeal for the power and the prerogatives of the Sovereign Pontiff is displayed, the Bishops united to him are not given their due respect, or sufficient account is not taken of their authority, or their actions and intentions are interpreted in a captious manner, without waiting for the judgment of the Apostolic See.

Similarly, it is to give proof of a submission which is far from sincere to set up some kind of opposition between one Pontiff and another. Those who, faced with two differing directives, reject the present one to hold to the past, are not giving proof of obedience to the authority which has the right and duty to guide them; and in some ways they resemble those who, on receiving a condemnation, would wish to appeal to a future council, or to a Pope who is better informed.

On this point what must be remembered is that in the government of the Church, except for the essential duties imposed on all Pontiffs by their apostolic office, each of them can adopt the attitude which he judges best according to times and circumstances. Of this he alone is the judge. It is true that for this he has not only special lights, but still more the knowledge of the needs and conditions of the whole of Christendom, for which, it is fitting, his apostolic care must provide. He has the charge of the universal welfare of the Church, to which is subordinate any particular need, and all others who are subject to this order must second the action of the supreme director and serve the end which he has in view. Since the Church is one and her head is one, so, too, her government is one, and all must conform to this.

When these principles are forgotten there is noticed among Catholics a diminution of respect, of veneration, and of confidence in the one given them for a guide; then there is a loosening of that bond of love and submission which ought to bind all the faithful to their pastors, the faithful and the pastors to the Supreme Pastor, the bond in which is principally to be found security and common salvation.

In the same way, by forgetting or neglecting these principles, the door is opened wide to divisions and dissensions among Catholics, to the grave detriment of union which is the distinctive mark of the faithful of Christ, and which, in every age, but particularly today by reason of the combined forces of the enemy, should be of supreme and universal interest, in favor of which every feeling of personal preference or individual advantage ought to be laid aside.

That obligation, if it is generally incumbent on all, is, you may indeed say, especially pressing upon journalists. If they have not been imbued with the docile and submissive spirit so necessary to each Catholic, they would assist in spreading more widely those deplorable matters and in making them more burdensome. The task pertaining to them in all the things that concern religion and that are closely connected to the action of the Church in human society is this: to be subject completely in mind and will, just as all the other faithful are, to their own bishops and to the Roman Pontiff; to follow and make known their teachings; to be fully and willingly subservient to their influence; and to reverence their precepts and assure that they are respected. He who would act otherwise in such a way that he would serve the aims and interests of those whose spirit and intentions We have reproved in this letter would fail the noble mission he has undertaken. So doing, in vain would he boast of attending to the good of the Church and helping her cause, no less than someone who would strive to weaken or diminish Catholic truth, or indeed someone who would show himself to be her overly fearful friend.

Your innermost thoughts, which we well know, and the discreet way in which you have valiantly conducted yourself in these very difficult times have moved us to discuss these matters with you, beloved Son, apart from the advantage they may have there in France. Ever firm and courageous in those matters of religion that are of importance and in preserving the sacred rights of the Church, you have, on a certain recent occasion that offered itself, vigorously protected them and fought in their defense with your distinguished and mighty voice. And what is more, you have adroitly coupled together with fortitude a calm and peaceful way of comportment worthy of the cause that you defend, maintaining a spirit free from disordered emotions and devoted completely to the mandates of the Apostolic See and to Us. It pleases us to show you proof again of our happiness and highest good will toward you. We are saddened only by the fact that your health is not such as we would strongly desire. We address our fervent petitions to God, and We pour out continuous prayers that He restore to you the best of health and that he keep you well for a very long time. And as a pledge of the divine favors that we call down in abundance upon you, from the deepest recesses of Our heart, We bestow Our Apostolic Blessing upon you, dear Son, and all your clergy and people.

Given in Rome, at St. Peter’s, on the 17th day of June of the year 1885, the eighth of Our Pontificate.

Leo XIII, Pope

Source: Acta Sanctae Sedis XVIII (1885): pp. 3-9. Translation into English by Novus Ordo Watch and Mother E. O’Gorman, RSCJ, in Benedictine Monks of Solesmes, eds., Papal Teachings: The Church (Boston, MA: St. Paul Editions, 1962).

Note: This document of Pope Leo XIII is also available as a PDF file: click here to download

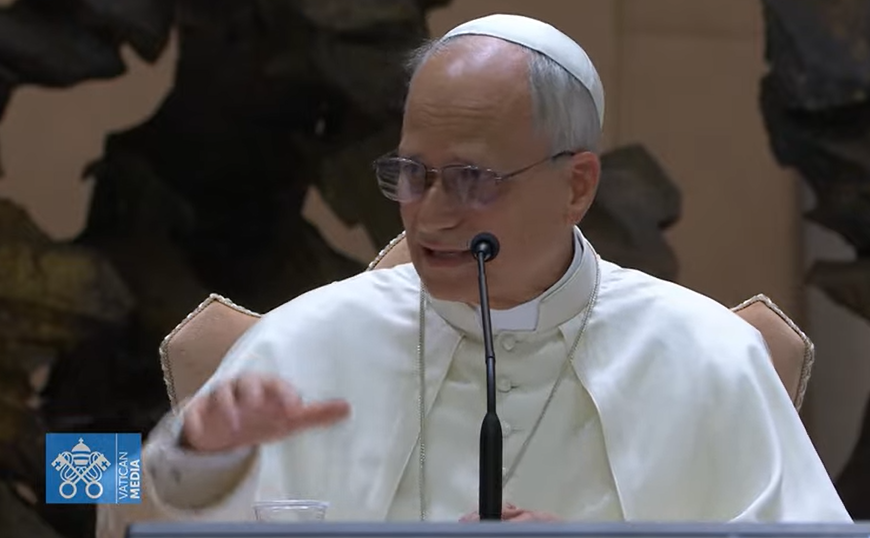

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

License: public domain